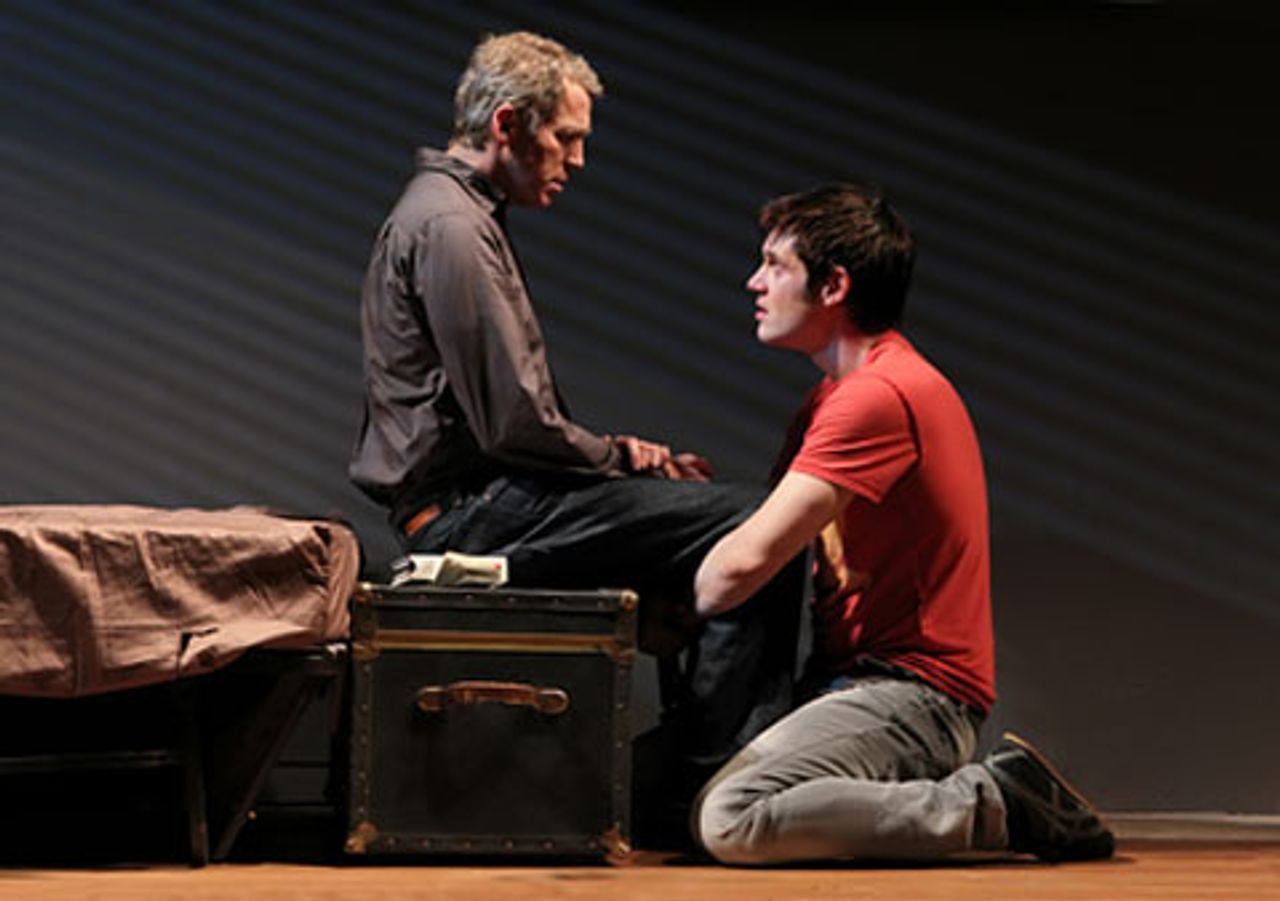

An Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism, with a Key to the Scriptures [Photo: Joan Marcus]

An Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism, with a Key to the Scriptures [Photo: Joan Marcus]

Tony Kushner’s play, An Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism, with a Key to the Scriptures, directed by Michael Greif, recently concluded a three-month run at New York’s Public Theater. The work, which garnered generally positive critical reaction, takes up unusual subject matter: the decline of trade unionism and the American Communist Party.

The central character is Gus Marcantonio (Michael Cristofer), a longtime member of the CPUSA and a retired Brooklyn longshoreman, who calls his three children—elder son Pier Luigi (nicknamed “Pill”), daughter Maria Theresa (M.T. or “Empty”) and younger son Vito (“V”)—together on the weekend of September 15-17, 2007, in an attempt to secure their approval and assistance in his plan to commit suicide. Most of the play is set in Marcantonio’s brownstone home, which has been in the family for generations.

Gus complains that he is suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, but it is clear to the audience as well as his family this is not the case. Alzheimer’s is in this instance an allegorical reference to “social forgetting.” What is being suggested is that humanity has forgotten its own recent history.

Gus feels deserted by history, and by the working class in particular. He has devoted his life, as he sees it, to the struggle for socialism. He has concluded, as he passionately explains to his family, that there is no class capable of doing away with the capitalist system, and has therefore decided, at the age of 72, that there is no purpose in living any longer.

There is much food for thought here. Kushner has often dealt with significant political and historical themes in his work, and his depiction of Gus and his generation is the strongest aspect of the play.

Portions of the dialogue, however, feel stilted and staged, perhaps a consequence of trying to provide background on historical and political matters not familiar to most of the audience. We are informed, for instance, that Gus is a cousin of Vito Marcantonio. The use of the Marcantonio name is no accident. Vito was a former New York City congressman from East Harlem who died more than 50 years ago, in 1954. Between 1938 and 1950, when the Republican, Democratic and Liberal Parties united behind a candidate to defeat him, Marcantonio was the representative of the American Labor Party (an alliance of liberals and Stalinists) in the halls of Congress. As one of the characters in the play explains, Marcantonio was probably never a member of the Communist Party, but he generally followed the party line.

The character of Gus is seriously and richly drawn. One gets the impression that Kushner knows people like this. The unflinching look at Gus’s demoralization, exhaustion and despair raises important issues about the history of the twentieth century. At the same time, having raised these important issues, Kushner’s work must be examined a bit more closely to see how deeply and honestly they are probed.

Gus does not understand why history took the turn that it did, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and, with that, his hopes for socialism. He says next to nothing about the role of the American Stalinists or the bureaucratic degeneration of the Russian Revolution. What he does say indicates that he has little interest, like most provincial American radicals, in these historical questions. He is cynical about what he considers the irrelevance of the Communist Party, but has no insight into why this is the case. The implication is that socialism has failed, and that capitalism, as rotten as it is, can rule indefinitely. As Gus angrily suggests to his children, it is the working class that has failed him.

It isn’t entirely clear from the play where Kushner stands on these issues. It is likely that he agrees, at least in part, with the outlook of his central character, although he obviously doesn’t share Gus’s suicidal conclusions. Of course it isn’t necessarily the playwright’s responsibility to fully explain or even to understand all of these issues, nor would a correct analysis of Stalinism necessarily make for more effective theater. The task would remain, of course, to find a way to translate these big historical questions into the drama and lives of his characters in a convincing manner. It must be said, however, that ignorance and confusion, to paraphrase Marx himself, never did anyone any good. Kushner is hampered by his own amorphous outlook.

There are some interesting exchanges. At one point Gus argues with his daughter, a labor lawyer active in Democratic Party politics, who tells him that his problem is rigidity. When Gus criticizes her support for Democrat John Kerry’s 2004 presidential campaign, she reminds him cuttingly that the CP supported Kerry as well.

None of this is developed, however. It is dropped as soon as it arises. There is no reference to the CPUSA’s slavish support for Roosevelt, its abandonment of any struggle for socialism in the interests of the Stalinist bureaucracy in the USSR. In a play whose central character has spent most of his adult life in the Communist Party, something more is called for.

At another point, Gus refers revealingly to the source of the bitterness that is eating away at him. He begins to talk about his own history as a trade unionist, as well as a CP member. After repeatedly boasting of his role in winning the GAI, or guaranteed annual income, for New York longshoremen displaced by automation in the 1970s, he admits that this deal, the supposed high point of his union struggle, abandoned all the younger workers, who got nothing and were thrown into the street. “When we agreed that some, not all, would get, we gave up the union, we gave up representing a class, we became…each one for himself.” This comment says something important about the evolution of the entire trade union movement in the post-World War II period.

Overall, however, the playwright is far too tentative in his treatment of these issues. Kushner has written a play of ideas, but he is somewhat cautious about how big to make these ideas, how much to confront his listeners or readers. One gets the impression that one of the intended audiences is a large section of the 1960s generation, and that disappointed and cynical ex-radicals would not be seriously challenged or offended, but simply nod in weary agreement.

Gus himself is of this later generation. He is not among the workers who built the unions in the bitter struggles of the 1930s, but were tragically miseducated and betrayed by the CP. His generation, coming of age at the time of the crisis of Stalinism in the 1950s, drew no serious conclusions and went on to make its peace with capitalism, even if some (like Gus) pretended otherwise. Gus’s despair is based in large part on a willful ignorance. It is the culmination of a life of political duplicity.

The role of Gus’s family raises other issues. They have been raised by a father in the Communist Party. The youngest, Vito (Stephen Pasquale), was largely sheltered from politics and has rejected his father’s traditions and views. The oldest, Pill (Stephen Spinella), is a history teacher and frustrated academic who is closest to his father’s outlook, but has relatively little to say about it. He has been working for many years on a Ph. D. thesis on the San Francisco longshore strike of 1934. Pill is gay, and his longtime partner is Paul (K. Todd Freeman), a black theology professor.

The middle child, Empty (Linda Emond), is a former nurse who became a labor lawyer and has some sort of government job. Her lesbian lover is another aspiring theologian, whose thesis adviser happens to be Pill’s partner Paul.

Despite the generally fine work of the actors, however, it must be said that the younger characters do not come to life as the elder Marcantonio does. We learn very little about the lives they have led or lead today. What we do see—including a strange subplot dealing with Pill’s appropriation of $30,000 that his sister had put aside for in vitro fertilization to have a child—stretches the limits of plausibility.

Tony Kushner

Tony Kushner

Kushner, who has often claimed socialist convictions, has become best known for writing about what is usually called the “gay experience.” While far from the first well-known playwright who is gay, he is assuredly the most prominent in the generation that matured in the wake of the dismantling, over the past 40 years, of many of the barriers and prejudices faced by homosexuals.

In this context, Kushner’s work reflects the contradictory and confused legacy of the protest movement of the 1960s and 70s. Much of what was confused in the earlier period became quite reactionary, when it took the form of self-absorbed identity politics. Rather than placing the legitimate and important issues of democratic rights within the framework of the struggles of the working class as a whole, race, gender and sexual orientation have been used to cultivate middle class layers hostile to the working class.

Kushner himself has not embraced the most blatant forms of this middle class politics, but neither does he reject them. He has undoubtedly been shaped and influenced by the recent decades in which identity politics has been built up to provide a social and political base for support to the status quo of inequality and privilege.

“An Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide…” seems directed toward several audiences. This in itself is not to be faulted, but the problem is that the two elements of the play do not cohere effectively as they are presented. The children do not come alive. They seem to exist as dramatic devices, illustrating the gulf between Gus and his children but not really illuminating their lives. Whatever the playwright’s conscious intentions, part of the audience will simply see itself in Pill and Empty, and leave it at that.

There are some suggestive elements, but they remain undeveloped. Pill and Empty’s names are undoubtedly meant to signify a certain hollowness or unhappiness in their lives. The fact that their lovers are theologians is a nod to the loss of “faith” they have lived through with the “end of socialism.” (Presumably, the last portion of the play’s full title, “with a Key to the Scriptures,” a reference to the quackery of Mary Baker Eddy of Christian Science fame, has some bearing on this same issue.) Pill and Empty oppose their father’s suggestion of suicide, but have few arguments to dissuade him.

Kushner’s Angels in America dealt with contemporary political problems in the age of Ronald Reagan. That play ended, revealingly, with fulsome praise for Mikhail Gorbachev as the harbinger of a new left-wing revival. Today, almost 20 years later, Kushner no longer speaks about Gorbachev, but seems to be registering mostly bewilderment.

The title of his play is an homage of sorts to George Bernard Shaw’s treatise, An Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism, written in 1928. Kushner is perhaps both acknowledging Shaw’s contribution to the drama of ideas, as well as expressing a certain sympathy with the latter’s Fabian socialist politics.

Kushner appears to hedge his bets, so to speak, in the final minutes of the play, with a hint of hope for the future. Gus speaks to the widow of a longshoreman, someone he worked with decades earlier. This woman eloquently describes the suffering of her family in the wake of the deindustrialization and loss of jobs for longshoremen and other sections of the working class. But under what circumstances does Gus happen to meet this woman again? It seems that she occupies herself these days with helping people to peacefully end their lives.

Ironically, the latest play is set in 2007, on the eve of the greatest global capitalist crisis in almost 80 years. As Kushner’s play opened in New York, there were unmistakable signs of the reemergence of mass political struggles around the world. It remains to be seen how this most political of contemporary playwrights will react to these changes, but if his latest play is any indication, he is in for some big surprises.