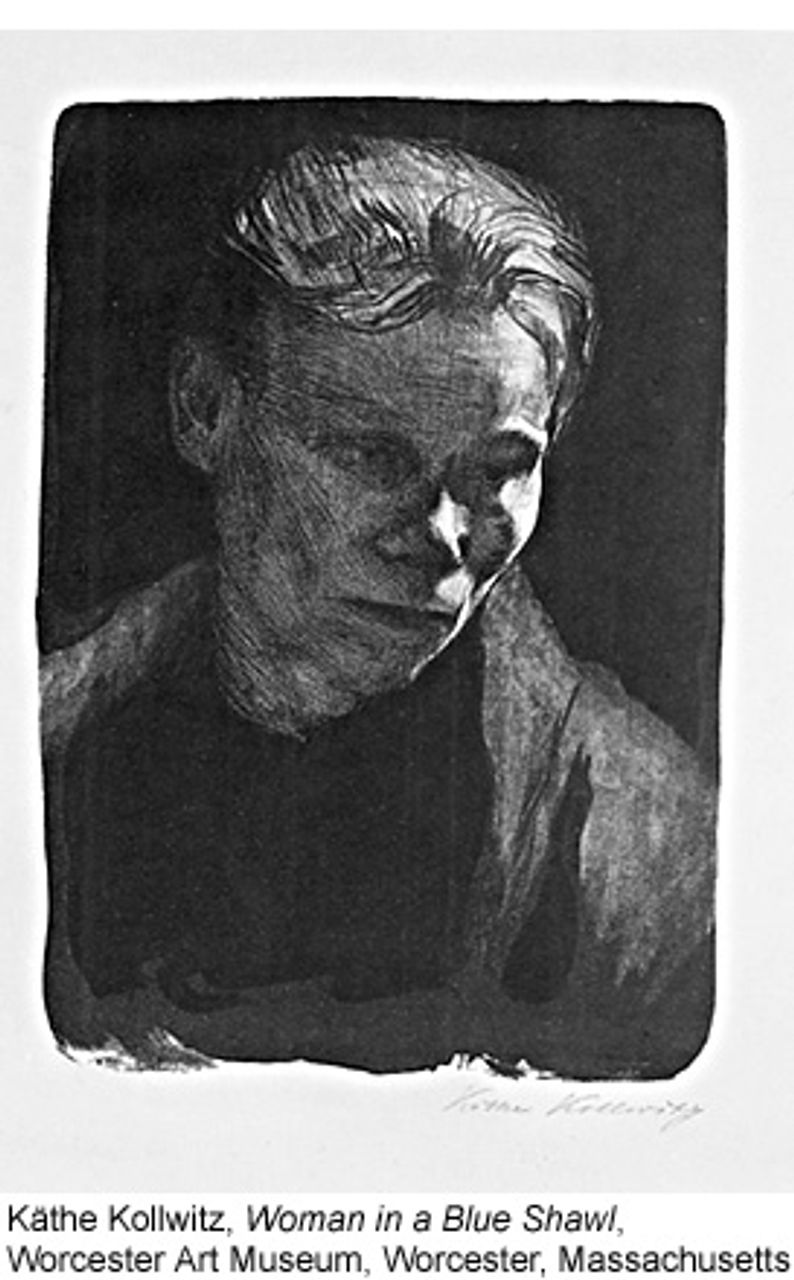

A lithography exhibition currently on display at the Worcester [Massachusetts] Art Museum features works by European masters (Goya, Delacroix and others) and nineteenth century lithographers (Daumier and Whistler)—as well as more modern artists. A piece in this last category is a 1909 print by German artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), entitled Woman in a Blue Shawl.

The darkly emotional lithograph of a middle-aged woman with a pensive but searing gaze captures many of the qualities of the laboring classes whose representation Kollwitz made her life’s work. The print reveals the artist’s commitment to depicting the working class as a social transformer, as the subject of events, shunning the more common approach of emphasizing its role as mere social victim.

Kollwitz’s subject is looking downward. The woman’s gaze is intimate and singular, yet its intensity extends beyond the immediate. Her worries, concerns, and in the far distance perhaps, her hopes, speak to the general human situation. She has been battered by society, but is the opposite of beaten. One senses that for every blow struck against her, the future reckoning will be deliberate and thorough. The lithograph is dignified, but nonetheless, packs an emotional and deep-going punch. Kollwitz insists on the strength and intelligence of her subject, despite the latter’s oppression.

Woman in a Blue Shawl exhibits the tremendous technical skill of its creator, dedicated to giving artistic expression to the conditions facing broad masses of the population. Kollwitz’s life and career, as much as that of any artist, were bound up with the growing self-consciousness of the German working class, its socialistic aspirations and its political organization, with all the latter’s strengths and weaknesses.

Käthe Kollwitz was born in 1867 in Königsberg, East Prussia. She grew up in a cultured atmosphere where critical thinking, directed toward social and moral idealism, was nurtured. The spirit of socialism encouraged by the Revolution of 1848 was venerated in the family, and her father, Karl Schmidt, joined the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), the party formed under the influence of Marx and Engels. Her elder brother Konrad Schmidt, who introduced her to Goethe, also became a leading member of the SPD. (In later years, she would remark, presumably indicating a goal she set out for herself, “One of the most striking things about Goethe’s life is his effort to get to know everything and take a position on everything.”) From early childhood, her father felt she was destined for a career in art, despite the “unfortunate” fact that she was a girl.

In 1891, she married Dr. Karl Kollwitz, her brother’s boyhood friend, who practiced a form of socialized medicine in a working class section of Berlin. World War I took the life of her son Peter, heightening the urgent emotionalism and anti-war character of her art. Kollwitz subsequently drew great inspiration from the Russian revolution. When Hitler assumed power in 1933, she was expelled from the Berlin Academy of Art; her works were removed from German museums and destroyed. Linked with socialists and communists, she faced hostility and increased restrictions, but was never imprisoned. Kollwitz died in the last days of World War II in 1945.

Lithography

Early on, Kollwitz was attracted to the graphic arts, as opposed to painting, as a medium. She felt it was of paramount importance that her work be moderately priced and widely accessible. Kollwitz passionately believed that art should be a means of communication, rejecting the notion of art for art’s sake.

She became an established artist when her print series, A Weavers’ Rebellion, created a major sensation at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition in 1898. Comprising six prints, the Weavers—a depiction of the 1844 revolt of Silesian workers—traces a dramatic pattern of poverty, death, conspiracy, a procession of angry weavers, the storming of the owner’s house and death by soldiers’ rifles.

“It was a landmark of class-conscious art: for almost the first time the plight of the worker and his age-long struggle to better his position received sympathetic treatment in pictures.... What Millet did with the peasant, she did with the worker—projected a way of life, envisioned a noble world.” (Prints and Drawings of Käthe Kollwitz, selected and introduced by Carl Zigrosser) The series earned her the ire of the Kaiser who, admonishing her work as “gutter” art, intervened to veto her gold medal award.

Kollwitz’s second print cycle was the Peasants’ War, which she worked on between 1902 and 1908. A rendition of the sixteenth century peasant uprising, the series emphasized, like A Weavers’ Rebellion, the intolerable conditions of the poor (in this case, the rural poor). What is unusual in the series is that in four of the seven plates, the protagonist is a woman. Increasingly, the urge to give voice to woman as the universal mother, protector and combatant was to find more complete expression in her work. The second print in the series, Raped, is one of the earliest pictures in Western art to portray the female victim of sexual violence sympathetically.

World War I

The impact of titanic events—World War I, the betrayal of Social Democracy (however Kollwitz may have perceived it), the sacrifice of her son to that war, the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the aborted German revolution of 1918-1919—forced Kollwitz to reevaluate the purpose of art and the relationship of technique to meaning in a work of art. She decided that many of the devices she had avidly used in previous works, such as intaglio, seemed irrelevant to the new requirements placed on art in times of war and social revolution.

Kollwitz wrote in her diary in 1919: “Lithography now seems to me the only technique I can manage. It’s hardly a technique at all, it’s so simple. In it only the essentials count.”

In 1919, Kollwitz executed a commission to memorialize the funeral of Karl Liebknecht, the leader, along with Rosa Luxemburg, of the revolutionary Spartacus League. Liebknecht and Luxemburg were both assassinated by reactionary soldiers, with the connivance of the right-wing SPD leadership in 1919, having opposed the imperialist war and defended socialist internationalism.

The Karl Liebknecht Memorial is a jarring piece in which Kollwitz captures the psychic devastation caused by Liebknecht’s murder in the working class. The woodcut presents workers somberly crowding around the corpse of the fallen leader, stoically paying their respects. Kollwitz renders the event with a combination of naturalism and symbolism, distilling the emotional mood of the population in the style of a Christian Lamentation.

In writing about the memorial to Liebknecht, Kollwitz exposes something of her internal artistic process: “As an artist I have the right to extract the emotional content out of everything, to let things work upon me and then give them outward form. And so I have the right to portray the working class’s farewell to Liebknecht, and even dedicate it to the workers, without following Liebknecht politically. Or isn’t that so?”

Part of her reflection on the grim consequences of war took the form in 1923 of a set of seven woodcuts, entitled War, illustrating the reaction of woman as wife and mother to the global slaughter of 1914-1918. The Volunteers, the most famous in the series, shows a group of four youth following a leader who is none other than Death. In 1916, Kollwitz wrote: “When I think I am convinced of the insanity of the war, I ask myself again by what law man ought to live.... I shall never fully understand it all. But it is clear that our boys, our Peter [her son], went into the war two years ago with pure hearts, and that they were ready to die for Germany. They died—almost all of them. Died in Germany and among Germany’s enemies—by the millions.... Is it a breach of faith with you, Peter, if I can only see madness in the war?”

She reprised the heart-rending, anti-war theme of a mother cradling a dead child in many different ways throughout her career.

Kollwitz’s views on the vicissitudes of German and international socialism in the twentieth century are not precisely known. She was first and foremost an artist of great honesty and seriousness, not a politician. However, her general sympathies can be gleaned from her public actions.

In 1924, Kollwitz participated in an exhibition of German art in the Soviet Union, and in 1927, on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution, she was invited to visit the USSR, now deep in the process of Stalinization. Lunacharsky, the remarkable “commissar of enlightenment,” discussed her work in his essay, An Exhibition of the Revolutionary Art of the West: “This truly admirable ‘apostle with the crayon’ has, in spite of her advanced years, altered her style again. It began as what might be described in artistic terms as outré realism, but now towards the end of her development, it is dominated more and more by pure poster technique. She aims at an immediate effect, so that at the very first glance one’s heart is wrung, tears choke the voice....

“As distinct from realism, her art is one where she never lets herself get lost in unnecessary details, and she says no more than her purpose demands to make an immediate impact; on the other hand, whatever the purpose demands, she says with the most graphic vividness.”

Prompted by a group of Russian artists, Kollwitz made a poster called Solidarity: The Propeller Song in 1932. “In order to make my position clear regarding an imperialist war against Russia, I drew this lithograph with the inscription: ‘We Protect the Soviet Union (Propeller Song),’ ” explained the artist.

During the second half of her career, Kollwitz created her famous anti-war posters, such as Never Again War! She also completed the memorial to her son Peter—a process that took 17 years—and focused on the theme of death in a final series of lithographs.

Toward the end of her life in 1941, Kollwitz summarized in her memoirs the source of her artistic and aesthetic commitment to the working class: “My actual motive, however, in choosing from now on the representation of the life of the worker was that selected motifs from that sphere simply and unconditionally were what I perceived as beautiful.... People from the bourgeoisie were entirely without charm for me. The bourgeois life seemed entirely pedantic to me. On the other hand the proletariat had great style.

“Only much later, when I became acquainted, especially through my husband, with the difficulty and tragedy of the depths of proletarian life, when I became acquainted with the women, who came to my husband seeking aid and incidentally also came to me, did I truly grasp in all its power, the fate of the proletariat....”

Again faced with the horrors of another world conflagration, Kollwitz demonstrated that despite the experience of fascism and Stalinism, she, unlike many artists at the time, never lost her bearings and succumbed to despair. One year before her death, in a 1944 entry in her memoirs, she writes: “Every war is answered by a new war, until everything is smashed.... That is why I am wholeheartedly for a radical end to this madness, and why my only hope is in world socialism.”

In her most tendentious art, in which she sought, through pointed emotionalism, to exhort to action, Kollwitz struggled with technique, always intent on subordinating means to end. For this reason, she returned to lithography almost exclusively from around 1920 until her death. This choice was not without difficulties because at times she seemed “to lose a certain critical distance from her subject, allowing them to hover precariously on the edge of sentimentality” (Kollwitz Reconsidered, Elizabeth Prelinger).

The best of Kollwitz’s last works are those in which her fluidity of style yields to visual economy, to images that are unsentimental but sympathetic.

Pure art versus tendentious art

In an era of abstraction, Kollwitz staunchly adhered to representational forms in her drive to depict the great questions facing humanity. “While I drew, and wept along with the terrified children I was drawing, I really felt the burden I am bearing. I felt that I have no right to withdraw from the responsibility of being an advocate. It is my duty to voice the sufferings of people, the never-ending sufferings heaped mountain-high,” penned the artist in 1920.

Single-mindedly driven to chronicle the depths of humankind’s anguish, Kollwitz declared in 1916: “A pure studio art is unfruitful and frail, for anything that does not form living roots—why should it exist at all?” And again in 1922: “One can say it a thousand times, that pure art does not include within itself a purpose. As long as I can work, I want to have an effect with my art.”

Kollwitz’s criticism of “pure art” has to be understood within a particular historical context. Marxists have not seen it as their task to favor, so to speak, tendentious art over “pure art,” but rather to understand the social and intellectual circumstances that give rise to one or the other at given historical moments.

The Russian Marxist Plekhanov associated the outlook of “art for art’s sake” with a mood of disappointment, connected with previous failures to radically transform the external world. This mood, which has objective roots, tends to produce a turn inward combined with an increasing fixation on the inner workings and purely formal side of the artist’s own activity.

Elaborating on this question, Plekhanov writes: “If the artists of a given country at one period shun ‘worldly agitation and strife,’ and at another, long for strife and the agitation that necessarily goes with it, this is not because somebody prescribes for them different ‘duties’ at different periods, but because in certain social conditions they are dominated by one attitude of mind, and by another attitude of mind in other conditions....

“The belief in art for art’s sake arises when artists and people keenly interested in art are hopelessly out of harmony with their social environment.... [T]he so-called utilitarian view of art, that is, the tendency to impart to its productions the significance of judgments on the phenomena of life, and the joyful eagerness, which always accompanies it, to take part in social strife, arises and spreads wherever there is mutual sympathy between a considerable section of society and people who have a more or less active interest in creative art.”

Kollwitz was an artist in sympathy with a considerable section of society, the socialist working class movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and she found support and intellectual sustenance in that general environment. For example, she wrote in her memoirs, “At such moments when I know I am working with an international society opposed to war, I am filled with a warm sense of contentment.”

She described this intense artistic and psychological engagement as being “gripped by the full force of the proletariat’s fate.”

From what type of soil does such a sensibility burst forth? How to explain her extraordinary sensitivity to and abhorrence of human suffering?

German social democracy

Kollwitz was born four years before the Paris Commune of 1871, a critical experience for the international working class. The last decades of the nineteenth century were characterized by an immense growth of the revolutionary self-consciousness of the working class, in Germany under the tutelage of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). In an effort to suppress the SPD, the Bismarck regime implemented anti-socialist laws between 1878 and 1890. These laws ultimately failed, and the period after 1890 witnessed an eruption of pent-up energy and activity.

In The Alternative Culture: Socialist Labor in Imperial Germany, Vernon Lidtke provides a picture of the vast array of SPD cultural and educational activities. Notwithstanding their many contradictions, these activities had a far-reaching impact on the lives and thinking of the most advanced workers and intellectuals, including artists. Whether or not Kollwitz was a direct participant, this was the crucial background to her intellectual and artistic development. It is impossible to fully appreciate her work apart from this history.

In 1891, the SPD founded the Berlin Workers’ Educational School. Kollwitz’s brother, Konrad Schmidt, was on the teaching staff in 1898-1899. In 1906, the SPD established a Party School at which a whole host of theoretical and historical matters were discussed, at which Franz Mehring and Rosa Luxemburg featured prominently as instructors.

More directly related to cultural life, Lidtke points to “the increasingly large network of voluntary associations (Vereine) affiliated with the Social Democratic party and the free trade unions. It was chiefly through these associations that Social Democrats and organized workers created the social and cultural environment that gave the labor movement so much of its distinctive profile in German society.”

He describes the far-ranging activities of at least 20 different kinds of associations, from gymnastic clubs and singing societies to naturalist groups and workers’ dramatic societies. In 1892, for example, delegates from 14 regional associations, representing 9,150 members in 319 workers’ singing societies, met in Berlin for their national congress.

Lidtke also lists artistic programs directly organized by the SPD in 1910-1913. During the 1909-1910 season, for instance, the party organized 97 poetry evenings, where the works of Goethe, Schiller, Heine and others were presented. The 1912-1913 musical season featured 159 concerts with 84,513 people in attendance, offering the music of Beethoven, Handel, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Wagner and others. A great expansion in workers’ libraries also took place. Never in history had an oppressed class systematically organized its own self-education and self-enlightenment. The sheer number of cultural organizations and events cited by Lidkte is itself inspiring.

The emphasis placed by the SPD on the cultural elevation of the working class was emphasized by Rosa Luxemburg in a letter to Franz Mehring written on the occasion of his 70th birthday in 1916: “For decades now you have occupied a special post in our movement, and no one else could have filled it. You are the representative of real culture in all its brilliance. If the German proletariat is the historic heir of classic German philosophy, as Marx and Engels declared, then you are the executor of that testament. You have saved everything of value which still remained of the once splendid culture of the bourgeoisie and brought it to us, into the camp of the socially disinherited. Thanks to your books and articles the German proletariat has been brought into close touch not only with classic German philosophy, but also with classic German literature, not only with Kant and Hegel, but with Lessing, Schiller and Goethe.”

In one fashion or another, Kollwitz’s efforts need to be seen associated with this socialist culture.

The collapse of German Social Democracy and the Second International were great blows to this cause. But they did not lead, in general, to despondency or despair. Millions of class-conscious workers viewed these events as betrayals of socialism and the principles that had guided their entire lives and the politics of their organizations. The betrayals of 1914 were “answered” by the October Revolution of 1917.

These experiences did not leave Kollwitz unscathed. In an April 1917 letter to her son Hans, she addresses the implications and lessons of these upheavals: “My dear Hans!... You know how at the beginning of the war you all said: Social Democracy has failed. We said that the idea of internationalism must be put aside right now, but back of everything national the international spirit remains. Later on this concept of mine was almost entirely buried; now it has sprung to life again. The development of the national spirit in its present form leads into blind alleys. Some condition must be found which preserves the life of the nation, but rules out the fatal rivalry among nations. The Social Democrats in Russia are speaking the language of truth. That is internationalism. Even though, God knows, they love their homeland.

“It seems to me that behind all the convulsions the world is undergoing, a new creation is already in the making. And the beloved millions who have died have shed their blood to raise humanity higher than humanity has been.”

Käthe Kollwitz recognized that her life’s artistic mission was to alert and sensitize others to the human condition. Endowed with a tremendous capacity for empathy and employing a consciously chosen epigrammatic form, she made clear her socialist sympathies in a variety of forms: historical settings, the immediate conditions of workers, in fierce anti-war agitation. In her memoirs in 1915, Kollwitz writes: “I do not want to go until I have faithfully made the most of my talent and cultivated the seed that was placed in me until the last small twig has grown.”

It can hardly be accidental that the life and work of one of the greatest female artists of the twentieth century were inextricably linked to the democratic, egalitarian cause of international socialism.

The exhibition at the Worcester Art Museum:

http://www.worcesterart.org/Exhibitions/lithographs.html

The Käthe Kollwitz Museum in Berlin (whose Web site contains numerous images):

http://www.kaethe-kollwitz.de/