Directed by Nick Broomfield, written by Broomfield, Marc Hoeferlin and Anna Telford

Nick Broomfield’s Battle for Haditha is opening in New York City this week. This comment on the film was originally posted as part of the coverage of the 2007 Toronto film festival.

Battle for Haditha is a genuine achievement. Nick Broomfield’s film is an effort to reconstruct the events and circumstances leading up to the massacre of 24 men, women and children by US marines in the Iraqi city of Haditha in November 2005.

The film, a dramatization of the episode, first follows the various participants—marines, Iraqi civilians, insurgents—as they go about their daily routines the day before the killings.

Local women with their children buy chickens for a party. A youngish Iraqi couple is focused on. The American marines patrol the city, expecting an attack from any quarter. They carry out raids, knocking down doors, terrifying and outraging the inhabitants. Their banter among themselves is coarse and super-aggressive. Two insurgents, one of them a former member of the Iraqi army, obtain an IED (improvised explosive device) and receive instructions on triggering it, by means of a cell-phone.

A good deal of the film, including perhaps its most memorable portions, is devoted to the processes which make the marines capable of carrying out their murderous assault. Battle for Haditha begins with one marine musing out loud, “I don’t why I’m here,” and expressions of alienation and demoralization continue throughout. “The marine corps don’t care, the country doesn’t care,” we hear. The individual marine has to learn to “act like a machine.” The Iraqis are “ragheads.” The marines chant, “Train, train, train, to kill, kill, kill.” They are indoctrinated to suspect and fear everyone: “This is a hostile environment.” Women and children, they’re told, are capable of carrying bombs.

We see an Iraqi man carrying a shovel over his shoulder. Someone claims he could be on his way to planting an IED; permission is granted, the man is blown to bits.

Meanwhile, Corporal Ramirez (Elliot Ruiz) is having nightmares and can’t sleep. He asks to see someone, a doctor. He’s told: not until your tour of duty is over. He explains he’s having bad dreams about the things he’s seen. Again: no doctor till your tour of duty’s finished.

It’s Ramirez who will lead the enraged attack on defenseless men, women and children when one of his favorites in the unit is blown up in a Humvee. The scenes of the massacre are chillingly and convincingly done; Broomfield bases them on eyewitness accounts from both Americans and Iraqis. After the IED goes off under the convoy, killing the one marine, a higher-up is consulted. His comment—“Take whatever action is necessary. I don’t want any more marines killed”—unleashes the atrocity.

Ramirez and his marines have already pulled a group of Iraqi men from a taxi stopped nearby and executed them. The families the film has been following have the misfortune to live in the houses near the IED attack. While the insurgents who planted the bomb are able to get away from their rooftop position, the marines burst into homes and kill the civilians, including small children, in cold blood.

After the initial killings, in one of the most horrifying sequences, marine snipers laugh and joke as they pick off a man running through a field. He’s the husband of the young Iraqi couple we’ve met before. His wife kneels over his body, hysterical. Ramirez offers her his hand, she spits at him. He goes and vomits. Later, in front of the other marines, though, he pretends to be fine. An officer leads prayers.

The next day, in his quarters, Ramirez suffers a kind of breakdown. The nightmares have continued. He keeps seeing bodies, women with kids. I have “to live with this guilt for the rest of my life ... I hate the officers who sent us in ... They don’t give a f—- about us,” he shouts.

The leader of the insurgents is pleased. “The Americans lost the battle ... Everyone is with us and we control the city.”

In a prologue, Ramirez is under arrest, charged with murder. The officer whose orders triggered the massacre presides over his fate. In a dreamlike sequence, Ramirez takes the hand of a small girl who survived the attack—two victims of the imperialist occupation of Iraq.

The film contains a number of remarkable and powerful scenes. It is not artistically perfect. Perhaps understandably, the writing of the Iraqi sections is somewhat weaker, a bit more schematic. Although Battle for Haditha was made with Iraqi actors (some of them professional stage actors) in Jordan, the filmmakers no doubt had a greater challenge in putting themselves in the shoes of ordinary Iraqis, much less fighters against the American occupation. The sinister figure of the ‘sheikh,’ the local leader of the insurgents, seems especially speculative.

All things considered, however, Broomfield and his collaborators have done an astonishing job. Best known for offbeat documentaries in which his own personality occasionally seemed to take center stage (Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madam, Kurt and Courtney, Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer), Broomfield has apparently opened a new chapter in his career.

The Guardian’s Paul Hoggart in a piece entitled “Mr. Wry gets serious,” cites the comments of Peter Dale of Britain’s Channel 4, which funded Battle for Haditha and Broomfield’s previous work, Ghosts, about the deaths of 23 Chinese immigrants in Morecambe Bay in 2004: “I think it’s part of a transition in Nick’s work from a slightly wry, off beat approach to a much more passionate and serious and political approach to his subject. In his more frivolous documentaries the joke had been wearing a little thin. Ghosts was a welcome return to form.”

Broomfield took great pains to represent the Haditha events accurately. Twelve of the performers playing US marines in his film are ex-marines. He also managed to speak to some of the marines involved in the Haditha incident. He told the Guardian reporter, “We spent five days in a motel in San Diego interviewing them for probably 10 hours a day, just to get a sense of their lives and who they really were. They were very wary to begin with, but once people start talking, they really talk. The main marine character we focus on was this guy called Ramirez. The night he got back from Iraq he broke into a truck and basically had post-traumatic stress and ended up driving into a house. He was best friends with the guy who was killed by the bomb, and then had the job of writing numbers on the dead people’s heads and photographing them. They were extremely tough and had seen a lot of action. They talked about chasing each other around with people’s legs and kicking people’s brains around.”

The filmmaker also stated that his team met with Iraqi insurgents who claimed to have been active in Haditha.

Broomfield ended up making the film for Channel 4 because he found no financing in the US. The Los Angeles Times noted in May 2007 that “Every Hollywood door he knocked at, he was told it was too soon for such a movie. ‘Everyone’s so worried,’ said Broomfield ... ‘They all wondered, “Does the American public have an appetite for this?””

The group of Haditha marines, in their conversations with Broomfield, explained the “standard operating procedure rules,” in the director’s words, under which they were operating. He told Time Out magazine, in an interview also published last May, “If, for example, a house is described as ‘hostile,’ then you just kill everyone in the house. It doesn’t matter if it contains two-year-olds or the elderly, which is what they did in Fallujah—where these guys had come from. ...

“I realised that these soldiers were very, very poor kids, who had all left school unbelievably early. It was the first time they had all been out of the United States. They didn’t speak a word of Iraqi. They had no idea what they were doing in Iraq, and they felt let down by the marine corps. It was hard to condemn them out of hand as cold-blooded killers. ...

“I think there have been lots of Hadithas, and there are lots of Hadithas every year.... The difference with this event is that the aftermath just happened to be filmed and now there’s an inquiry. It’s much more convenient for the US government and the marine corps to make scapegoats of these guys than actually deal with its policy and rules of engagement in Iraq. I’m sure it happens on a lesser scale every single day.’”

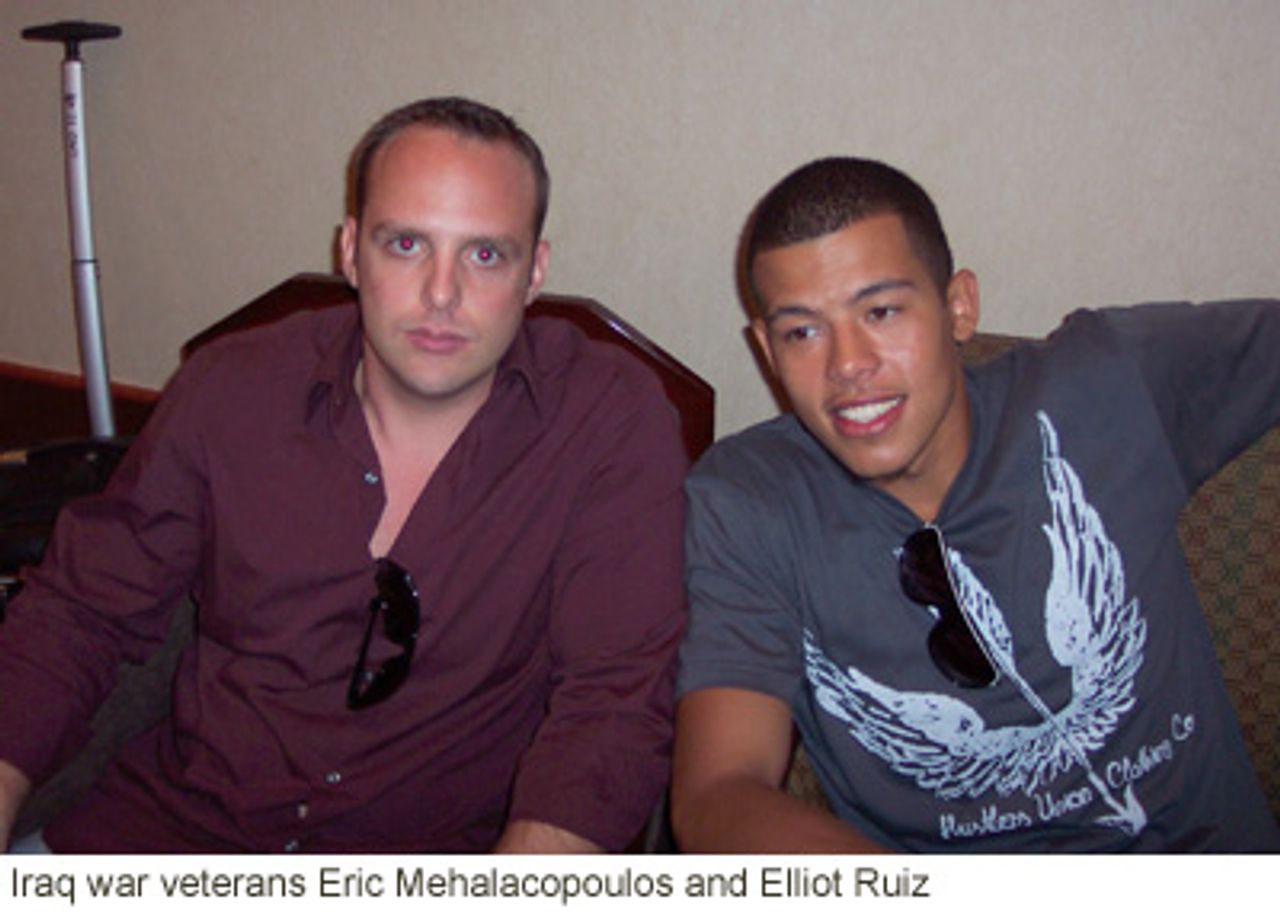

A conversation with two Iraq war veterans

I spoke to two of the former marines in Broomfield’s film in Toronto. Elliot Ruiz, born in Philadelphia, plays Corporal Ramirez and Eric Mehalacopoulos, born in Montreal, Quebec, plays Sergeant Ross. I asked Ruiz about his experiences in Iraq.

He explained, “I was 17 when I was sent to Iraq, during the initial invasion. We pushed all the way up to Tikrit and I ended up being wounded, I almost lost my life. It’s crazy, people don’t know the type of things that we go through. That’s what I like about the film, it shows that.”

I noted that film showed how the marines were whipped up into a frenzy and brutalized. I asked the pair if they had helped write or prepare any of the script.

Ruiz said, “No, but a lot of it was improvisation. Nick [Broomfield] just told us, ‘This is what’s happening in this scene, this is what I need,’ and mostly everything was improvised.” Mehalacopoulos added, “We used our experiences as the basis of it.” I commented, “So what we see is accurate?” Ruiz replied, “Yes.

I asked them both what they would like audiences to draw from the film.

“Like I said earlier,” Ruiz observed, “I just want the audience to take a look and see what we go through on a day-to-day basis. You might lose a friend, but you have to keep moving. It’s your job. A lot of people don’t understand that. I also hope that they see what the Iraqis go through on a day-to-day basis, you know.”

Mehalacopoulos continued, “As we speak, this is going on. The film only shows a little bit, there’s so much more to tell. I think it’s a movie that’s going to make people think, and that’s what important.”

I pointed out to Ruiz that the spectator finds himself horrified by the crimes Corporal Ramirez commits, but at the end he manages to be a sympathetic character. “The American soldiers themselves are victims,” I said.

Ruiz: “Exactly.”

Mehalacopoulos: “We were put there. We chose to enlist, and therefore we’re going to do our job and carry on the mission, and all that’s fine. But you ask 90 percent of the guys, they’d rather not be there.”

I suggested that no marine or soldier guilty of crimes should be absolved. “Those who are responsible for crimes are responsible for crimes, but the ultimate responsibility is above.” Mehalacopoulos agreed.

I asked them what they thought the war was about. Mehalacopoulos ventured, “It’s tricky, because there’s so much stuff that’s hidden from us, I think. A lot of people say oil. Who knows? It wasn’t what people were told, that wasn’t the real reason. There was a lot of lying, and that’s what’s not fair. All those families that lost their sons, brothers, husbands, whatever. It’s not fair. To die for a rich man’s, a powerful man’s cause. That’s throughout history. Big business ...”

Ruiz went on, “If people saw this, it would change the way a lot of people think. That’s what I like about this film, it doesn’t hold anything back. It shows what happens on a day-to-day basis out there.”

Both former marines praised Broomfield. Ruiz said, “Working with him was wonderful. He stepped back and just let us be us. And that’s what brought the authenticity to the film.”

I asked Ruiz about the scene of Ramirez’s breakdown, where the character curses the officers who have obliged him to commit actions he will feel guilty about for the rest of his life—had this scene been based on his own experiences and feelings?

“I mean, I was 17, I almost lost my life out there. Who wouldn’t be angry toward that? Working on this film, and being able to go back to Jordan ... People don’t understand, we were dropped in a combat zone in an Arab country. The things that happened to us, of course we felt a certain way toward the Arab people, or the Iraqi people.

“Going back to Jordan and being able to meet these people, see these people, live with these people on a day-to-day basis, totally changed my opinion and the way I thought about them. It was a wonderful experience. I never thought I’d be able to live with an Iraqi. I lived with an Iraqi. We shared the same bathroom. We joked around, he ended up being one of the nicest people I’ve ever met in my life, man. He was happy about everything. He didn’t care, it could be the worst day in the world, and he was happy.”

Mehalacopoulos continued, “It’s a people that’s been through a lot. And a lot more than anyone in the US probably. And they have so much pride because there’s so much culture and history, you know, the cradle of civilization, right?”

I noted there had been a propaganda war to paint all Arabs as terrorists. Ruiz nodded. “It took me going back to Jordan, another Arab country, to realize that. It’s a shame it took that, but that’s the reality. Thank god I went back to Jordan and got to spend time with the people and the culture.”

I noted that the Iraqis had every right to resist a foreign army of occupation. Mehalacopoulos said, “And they’re not going to stop fighting. I knew this from the beginning, because we got to a hospital in Baghdad. A doctor, a well-educated man told me, he predicted what was going to happen. He was totally right, and this was in the first few days of the war. You know what I’m saying? They know their people better than we do.”