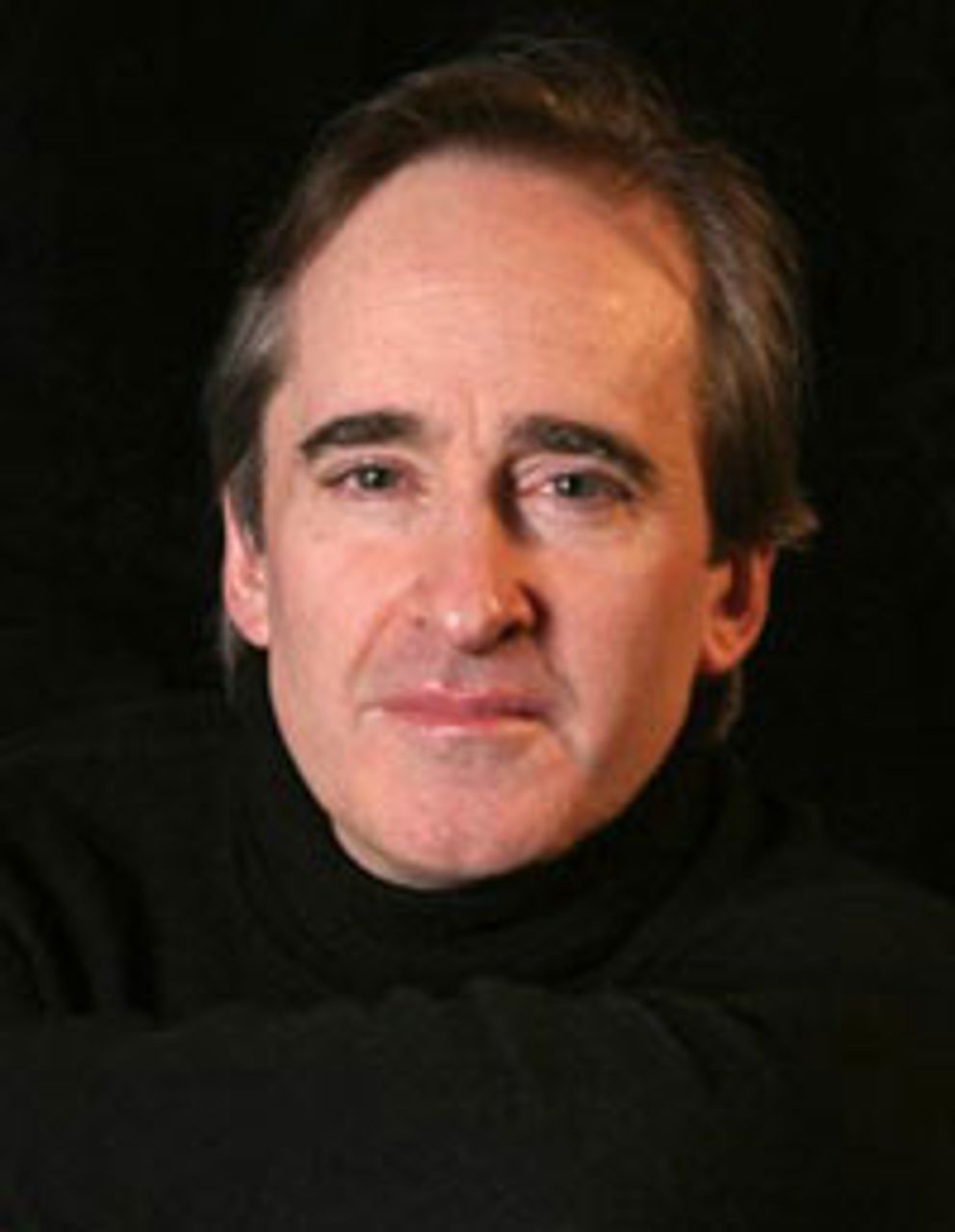

James Conlon

James ConlonClassical works by composers who died at the hands of the Nazis or who were forced to leave the lands of their birth, in some cases never to return, have been receiving increased attention in recent years. James Conlon, an American-born conductor with a long and fruitful career in both Europe and the U.S. and now the music director of the Los Angeles Opera, has taken the lead in this project to rescue unjustly neglected and in some cases unknown work.

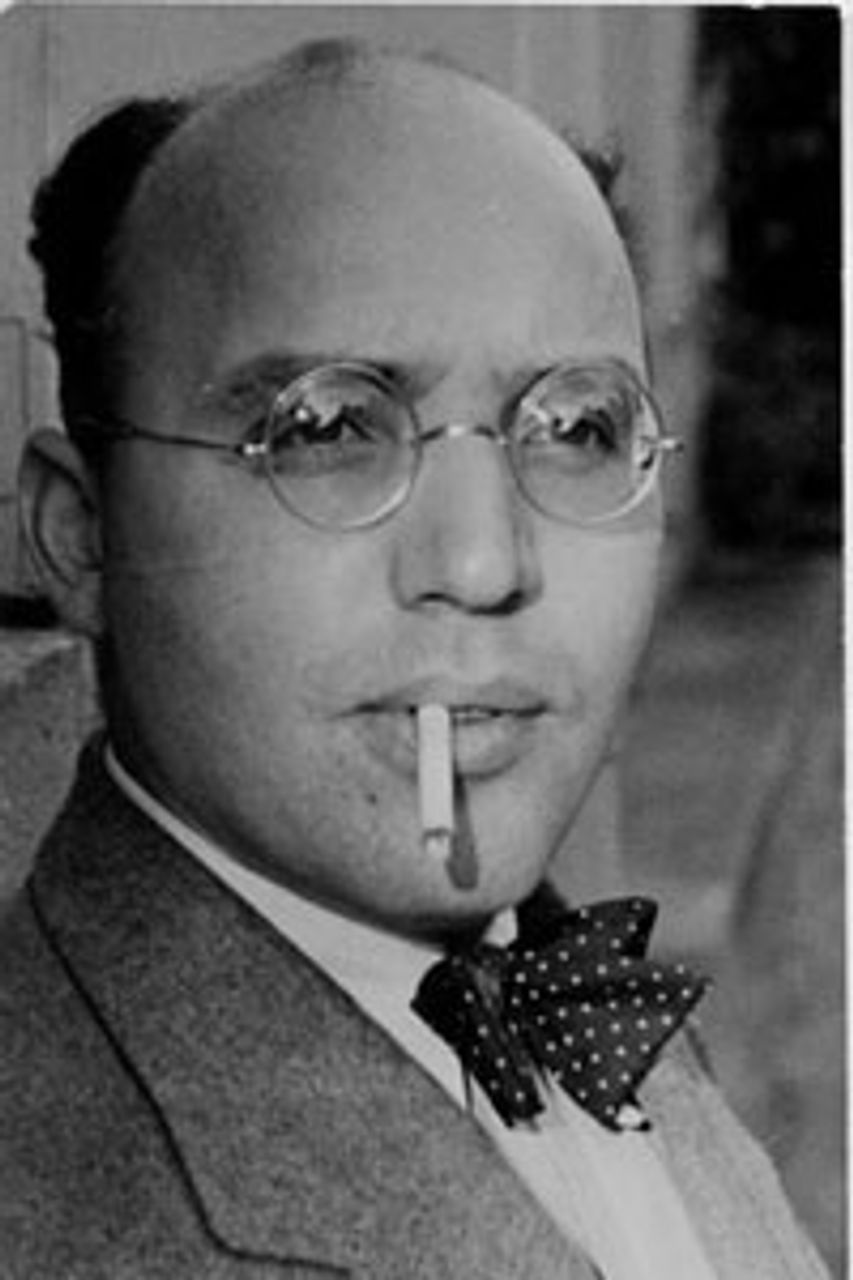

The list of the musical victims of Nazism is a long one. It includes well-known figures like Kurt Weill, the collaborator of Bertolt Brecht in The Threepenny Opera and other works, who came to America in the mid-1930s and had a successful career on Broadway until he died at the age of 50 in 1950. Other émigrés, like Erich Korngold and Friedrich Hollander, had some success in Hollywood. Some of the older generation, like Alexander Zemlinsky, Arnold Schoenberg’s brother-in-law, who was in his late 60s when he came to New York in 1938, were unable to find their footing in America.

Kurt Weil

Kurt Weil

Noted composers in the 1930s, if they were Jewish or opponents of fascism, were demonized by the Nazis in the notorious Entartete Musik (Degenerate Music) exhibition in Düsseldorf in 1938, which was patterned on the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) in Munich a year earlier. While the Hitler regime naturally denounced the musical avant-garde, the work of some of the most famous musicians in the German musical tradition also had to be excluded. The bizarre efforts by the Nazis to rewrite the history of German music in order to repudiate the historic role of German-Jewish composers and musicians, including Mendelssohn and many others, is a subject which deserves separate treatment.

One point should be clearly understood: these composers worked squarely in the German classical tradition. As Conlon has explained, they were “an integral part of German music.… They have the same roots and came out of the same environment as everyone else in their time.” This is what made the Nazi cultural campaign so utterly reactionary and historically doomed, despite the awful crimes that were carried out.

While many were forced to flee fascism, there were other composers, especially those who were younger and lesser known, who for various reasons could not or did not leave in time. Erwin Schulhoff, Hans Krasa, Victor Ullmann and others perished in the concentration camps. (See The rediscovered music of Erwin Schulhoff.)

Concerts featuring the work of these lesser-known figures were a rare event until recently, but they have become increasingly common, and other individuals and musical organizations, including the American Symphony Orchestra under Leon Botstein, have joined Conlon in promoting this “lost music” of the twentieth century.

Several recitals in the past few months in New York City stand out in this regard. In November, a series of four concerts and three lectures on the theme of “Music in Exile: Émigré Composers of the 1930s” was presented by the ARC Ensemble (Artists of the Royal Conservatory) of the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, led by its artistic director Simon Wynberg. James Conlon is honorary chairman of the ARC Ensemble.

These programs, which coincided with the 70th anniversary of Kristallnacht, the anti-Semitic pogrom organized by the Nazi regime throughout Germany on November 9, 1938, took place in New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage. They included works that are hardly ever heard in the concert hall. One recital, for instance, featured works by composers from different backgrounds and even generations who found refuge in Britain. The program consisted of a suite for violin and piano by Robert Kahn, a friend of Albert Einstein, who was born in 1865 and who met and impressed Johannes Brahms in the 1880s; a divertimento for clarinet and string quartet by Matyas Seiber, a Hungarian for whom Béla Bartók had the highest regard; and a piano quintet by Franz Reizenstein, a German who studied with Paul Hindemith.

Mieczyslaw Weinberg

Mieczyslaw Weinberg

This writer attended a concert devoted entirely to the work of Mieczyslaw Weinberg (1919-1996). Weinberg stood out among the composers featured in this series because, unlike the others, he sought refuge in the East, not the West. Born in Warsaw, he graduated from that city’s Conservatory just before the Nazi invasion. Weinberg continued his studies in Minsk, the capital of what was then the Byelorussian Soviet republic and is now Belarus. Like many other artists and intellectuals, he spent part of the war away from the front, in Tashkent, in the republic of Uzbekistan.

Weinberg became the son-in-law of the esteemed Soviet Jewish actor and director Solomon Mikhoels. Mikhoels later became a victim of Stalin’s anti-Semitic paranoia and persecution in the post-World War II period, murdered in 1948 in an incident that the regime first staged as a car accident.

Solomon Mikhoels

Solomon Mikhoels

It was Mikhoels who in 1943 recommended Weinberg and his work to Dmitri Shostakovich, the most famous Soviet composer. Shostakovich became Weinberg’s lifelong friend and supporter. When Weinberg was arrested in January 1953, in what turned out to be the last spasm of Stalin’s purges, Shostakovich took the daring step of writing to Stalin himself to protest Weinberg’s innocence. The composer was released from prison when Stalin died less than two months later.

Weinberg lived until 1996 and composed prolifically, including 26 symphonies, 17 string quartets, 19 sonatas and 150 songs. However, although he was well known in musical circles in the USSR and counted cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, violinist David Oistrakh and pianist Emil Gilels among the famous musicians who performed his work, he was almost completely unknown outside the Soviet Union. In recent years, this has changed, and several dozen recordings of his work are available. At least one commentator considers him “the third great Soviet composer, along with [Sergei] Prokofiev and Shostakovich.”

The Weinberg program consisted of two early works—a sonata for clarinet and piano and a piano quintet, both completed when he was about 25 years old, soon after he met Shostakovich—and a much later work, a song cycle for bass and piano, “From Zhukovsky’s Lyrics,” based on words by the famous nineteenth century Russian romantic poet Vasily Zhukovsky, and composed in 1976.

All three compositions made a favorable first impression. The clarinet sonata is a three-movement work that, unusually, closes with an Adagio slow movement. The clarinet in this sonata is used to express some of the atmosphere and thematic quality of Jewish klezmer music, with which Weinberg was well acquainted from his youth.

The quintet is a major work that has much in common, certainly in terms of mood, with the emotions conveyed by Shostakovich in his chamber music. Its composition is roughly contemporaneous with Shostakovich’s bleak 8th Symphony and his wonderful Second Piano Trio, Op. 67, with its use of Jewish folk themes.

Weinberg’s music shares with that of Shostakovich some of the same abrupt shifts of mood, tone color and rhythm. In the work of both composers, however, these changes rarely feel forced. The sardonic elements combine with the lyrical and the desolate to communicate something of what it meant to live through this period of mass killings of the Jews of Europe, as well as the deaths of some 20 million Soviet citizens.

* * * * *

A few days after the ARC Ensemble concerts, a very different program on the same general theme was presented in Manhattan by the New York Festival of Song (NYFOS). This one was called “Fugitives.”

The NYFOS was founded 20 years ago by pianists Michael Barrett and Steven Blier. It is a much-admired group that has presented nearly 100 programs over this period. In its own words, each program is “unified by a theme, drawing together rarely-heard songs of all kinds, overriding traditional distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low’ performance genres, exploring the character and language of other regions and cultures, and the personal voices of song composers and lyricists.”

The November recital was, to put it simply, a wonderful one. The program, with Blier at the piano joined by young mezzo-soprano Kate Lindsey and tenor Joseph Kaiser, consisted of 22 songs by 11 different composers. Its first half concentrated on work composed in Europe by musicians who would soon be forced to flee for their lives. These included the famous and well known, among them Arnold Schoenberg (“Erwartung” [Expectation]), Alexander Zemlinsky (“Altdeutsches Minnelied” [Old German Love Song] and “Meeraugen” [Eyes on the Sea]) and Franz Schreker (“Unendliche Liebe” [Eternal Love]). These songs are very much in the German lieder tradition, and date from the very early years of the twentieth century.

Alexander Zemlinsky

Alexander Zemlinsky

In the second half of the program, the scene shifted to the work of several composers who died in the camps (Hans Krasa and Victor Ullmann), as well as songs composed by musicians in exile in New York or Los Angeles. The latter group included some who were represented on both halves of the program: Kurt Weill, Hanns Eisler, Friedrich Hollander and Erich Korngold. Weill was represented on this part of the program with a song from Knickerbocker Holiday, one of his Broadway shows, and “Wie Lange Noch?,” a haunting love song whose words could be understood as a reference to Hitler and his false promises to the German people.

While this wide-ranging program included art songs, cabaret songs and songs from the theater and even the movies (“Black Market,” written for Marlene Dietrich in A Foreign Affair), there was a strong political theme, as Blier observed in his program notes. Referring to Weill, Eisler, Hollander and Kurt Tucholsky, Blier writes that “Germany’s brilliant cadre of political satirists was considered the most ‘degenerate’ of all the Entartete musicians—and the most dangerous to the Third Reich.”

Kurt Tucholsky

Kurt Tucholsky

Weill, as noted above, collaborated with Brecht in some of his most powerful work. Kurt Tucholsky (1890-1935) was a left-wing journalist and writer who committed suicide in exile in Sweden. Hollander (1898-1976), a popular songwriter who later prospered in the US, was represented on the NYFOS program by two songs, one of them the hilarious “Wenn der alte motor wieder tackt” (When the old car starts up again), performed with energy and brilliance by Lindsey, Kaiser and Blier. With words by Tucholsky, this includes bitter satirical references to the hyperinflation and political crisis of the Weimar Republic, including a mention of Gustav Noske, the right-wing Social Democrat who played the key role in facilitating the assassination of revolutionary leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in 1919.

Hanns Eisler

Hanns Eisler

Hanns Eisler (1898-1962) was the most heavily represented in the song recital, with four songs to his credit. He was also the most politically committed of the composers on the program. It is impossible within the scope of this review to consider Eisler’s career in the depth it deserves, but the NYFOS was certainly correct to highlight his work.

A star pupil of none other than Schoenberg, Eisler soon turned his back on atonality and the 12-tone system of his teacher. As a young man he declared himself a Marxist, and began a lifelong collaboration with Brecht. A member of the German Communist Party, he became especially well known for his Kampflieder—songs of struggle.

Eisler’s brother Gerhart became a notorious Stalinist operative, and his sister Ruth Fischer, who had been a leader of the German CP in the 1920s, later became, in American exile, a disillusioned anti-communist. The musical Eisler remained loyal to Stalinism. This could not help but have a deleterious effect on his work, but he also wrote some imperishable music that is rooted in its time and place. His music had enormous passion, originality and integrity.

The composer found himself in Hollywood in the 1940s, where he did some work that did not interest him and where he was understandably unhappy. In 1948, however, with the Cold War in full swing, he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and quickly deported to what was soon to become Stalinist East Germany. For the remaining 14 years of his life, Eisler grew progressively more disillusioned with the Stalinist regime, and his work was hampered by the ruling bureaucracy.

One of Eisler’s Kampflieder was presented in a stirring rendition at the NYFOS recital. The following is an English translation of the concluding verses of the anti-war anthem “Der Graben” (The Trenches), with words by Tucholsky.

Don’t be proud of your decorations and medals!

Don’t be proud of your battle scars and your era!

You were sent to the trenches by the landed aristocrats,

The madness of the statesmen,

And the greed of manufacturers!

You were good enough to be carrion for ravens,

For the grave, comrades, for the trenches!

Think of the death rattle and the moans of pain.

Over there live fathers, mothers, sons,

Eking out a living, like you, the best they can.

Won’t you offer them your hands?

Stretch the hands of brotherhood

As the most precious of gifts

Over the trenches, my people, over the trenches!

* * * * *

It should be readily apparent that something more than the opportunity to hear some interesting music is involved in concerts like those described above. In an introductory note to the program booklet for the “Music in Exile” series, James Conlon discusses “three aspects to be taken into consideration in performing this music: moral, historical and artistic.”

The moral element is explained by Conlon as paying tribute to great artists who lost their lives and fell victim to racial and religious hatred. He also correctly notes that these considerations would not “be reason enough for revival were it not for the artistic quality of what was lost,” and that this quality cannot be judged by a single hearing, but only “after those performing and listening over the course of years have given the spirit of that era sufficient time to be fully digested.”

The historical aspect of the question is in some ways the most crucial, although it cannot be separated from the artistic. What Conlon writes about this provides much food for thought.

“The suppression of these composers and musicians caused the greatest single rupture in what had been a continuous seamless transmittal of German classical music,” Conlon declares. “This centuries-old tradition, dating from before Johann Sebastian Bach, was passed on from one generation to the next. It was nourished by the free expression of an often contentious creative exchange between conservative traditional modes of expression and competing currents of innovation and iconoclasm. The politics of the Third Reich destroyed the environment in which this interchange could flourish, murdering an entire generation of its greatest talents, uprooting a garden with its creative polemics and dialectics, forcing those who survived to scatter where there was no comparable artistic milieu in which to live and create.”

The development of music, like all social, political and cultural phenomena, follows a dialectical path. The whole history of music shows the futility of trying to understand it by simply upholding “conservatism” or “innovation” in principle. It is not a matter of prescribing the “correct” path in music, or of fostering some kind of bland, eclectic combination of opposing trends. The “contentious creative exchange” is what is key. This is what the Third Reich obviously destroyed. Stalinism also worked ferociously to strangle the creativity of artists and musicians; but precisely because the Soviet regime had revolutionary origins that had not yet been completely destroyed, composers like Shostakovich and Prokofiev found a way to contribute to the musical heritage of humanity.

In the more than 60 years since the end of the Third Reich, more and more composers, performers and listeners have begun to grasp the lasting cultural damage done by the reactionary chauvinism and nationalism that was the ideological underpinning of fascism. What happened is that the “innovators” and “iconoclasts” that Conlon refers to in many cases lost their own historical framework, musically speaking.

It isn’t a matter of blaming the individual artists. They too suffered from the interruption in the classical tradition. They worked in a climate in which the music of the nineteenth century was to some extent artificially cut off from its development in the twentieth. This was at any rate the case in Germany and Central Europe. This was one element that helped to foster the rise of academicism in the postwar decades, the tendency to discount the importance of appealing to a broader audience, and of fighting to raise the cultural literacy of the masses of people, which had always been associated with the growth of the mass socialist movement.

The fact that the music of the first half of the twentieth century is being reexamined and rediscovered is a sign of growing cultural awareness and ferment. The political themes of German composers like Eisler and others obviously resonate today, as the program notes for the concerts discussed above acknowledged.

Contemporary classical composition still suffers far too often from the blandness already referred to, but some patience is called for. If, as Conlon writes, the “spirit of that era” (the interwar period, in particular) needs “sufficient time to be digested” before its music can be fully appreciated by listeners, that of course also applies to composers. They will, in their own way and by their own means, come to terms with the spirit of the earlier era and also with that of their own time, and this will make possible new creative development. New music will challenge the old traditions but will not simply reject them or, worse yet, work in ignorance of their existence or their historical importance.

It is also obviously not a matter of complacently celebrating the place of classical music or the arts in general in contemporary capitalism. Stunted bourgeois democracy, where everything has its price and ignorance and backwardness are worshipped, has its own ways of distorting, strangling and inhibiting the creative impulses of millions, first of all by denying the vast majority the opportunity to develop their potential abilities. Music cannot develop in the kind of narrow and privileged atmosphere that has characterized so much of cultural life in recent decades. The future of music is bound up with the broader cultural and political development of the masses of working people, as well as the conscious assimilation by musicians and composers of the history of music itself.