PART ONE | PART TWO | PART THREE | PART FOUR | PART FIVE

Purchase this essay as a pamphlet on Mehring Books.

The PATCO strike began on August 3, 1981. About 85 percent of air traffic controllers in the US voted in favor of the strike, and 15,000 of 16,000 walked off the job.

The response of the Reagan administration made clear that the plan to crush the controllers’ union had been worked out well in advance. President Ronald Reagan immediately invoked a rarely-used national emergency clause of the anti-working class Taft-Hartley Act, passed in 1947, which fired all workers who did not return to their jobs within 48 hours.

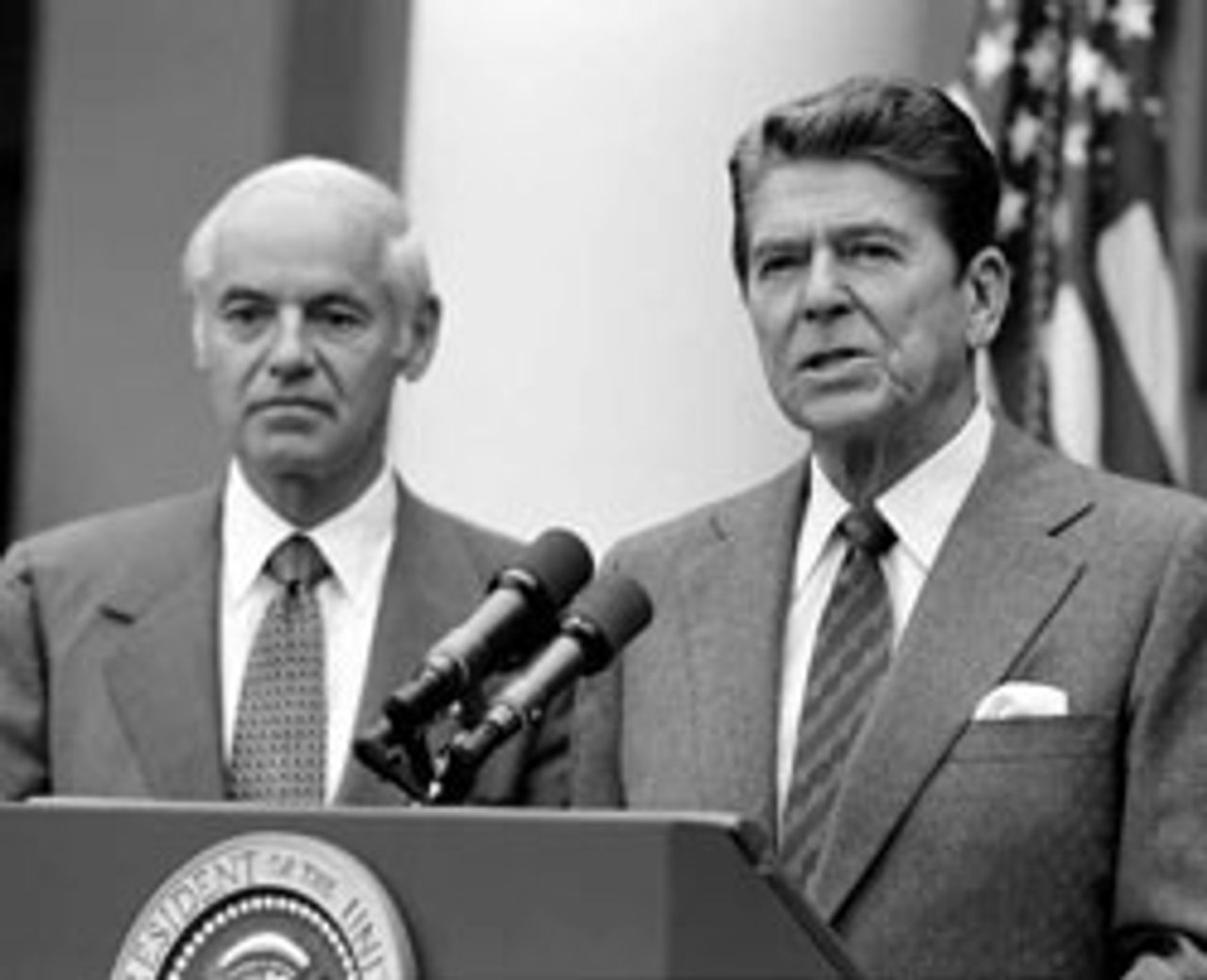

Reagan (right) with Drew Lewis, Secretary

Reagan (right) with Drew Lewis, Secretaryof Transportation

To continue air travel and commerce, albeit at a significantly reduced level, Reagan deployed thousands of military air traffic controllers as scabs. The administration secured a court order declaring the strike illegal, making it possible to jail strike leaders and fine rank-and-file workers, and making the disbursement of union funds for strikers illegal. The National Labor Relations Board immediately filed a suit seeking the decertification of PATCO. FBI agents and federal marshals were deployed to picket lines to photograph and otherwise intimidate the strikers.

Reagan also ordered Secretary of Transportation Drew Lewis not to negotiate with PATCO. In other words, the government sought one and only one outcome: the destruction of the union.

The deadline for Reagan’s back-to-work-or-be-fired threat came on the morning of Wednesday, August 5, at 11 a.m. When the clock struck 11 and the mass firing became official, thousands of air traffic controllers in union halls, picket lines, and parks across the country erupted into chants of “Strike!, Strike!, Strike!”

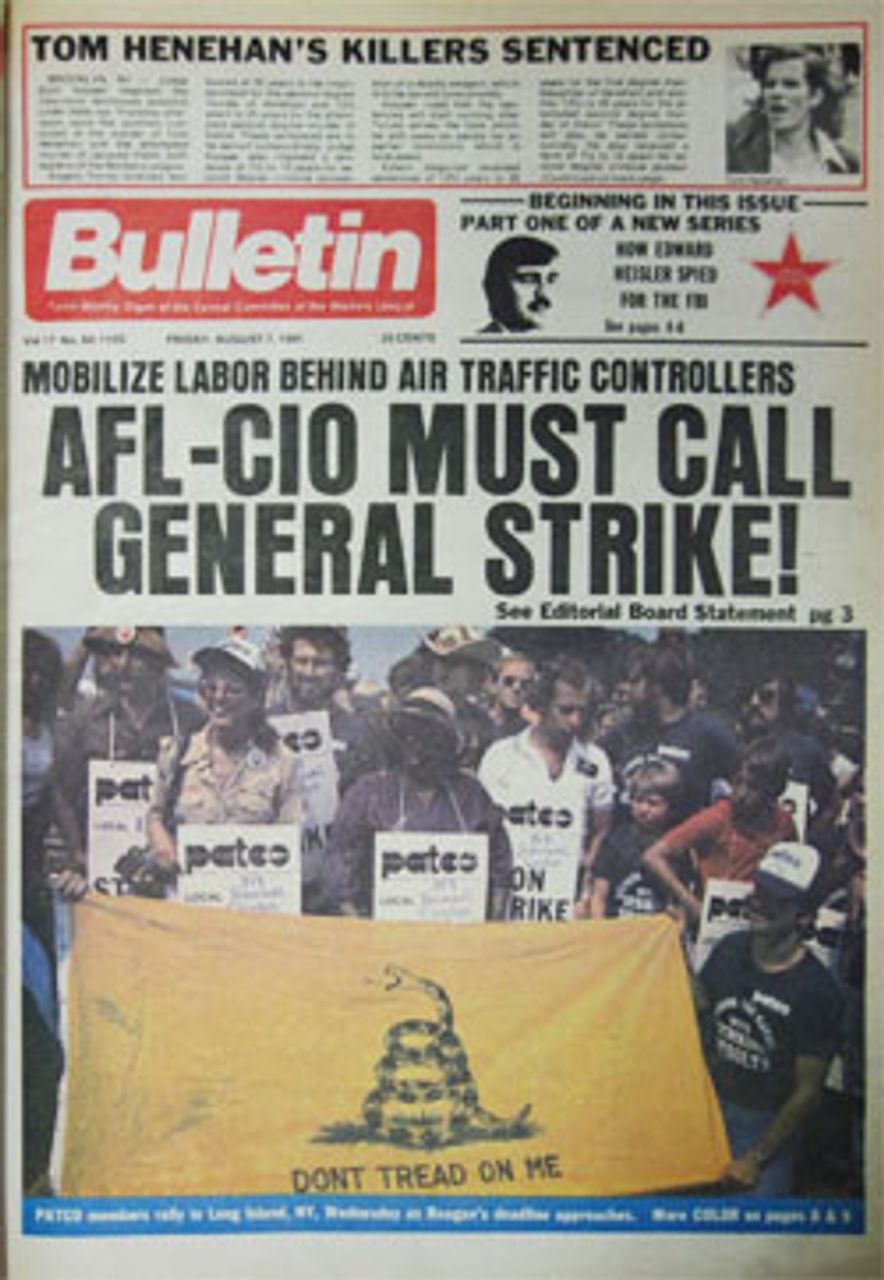

Hundreds of air traffic controllers from New York City’s terminals, along with supporters, rallied in East Meadow, Long Island. Gathered in a circle, they thrust their fists into the air in defiance as the deadline passed. In the middle stood six strikers holding a large, “Don’t Tread on Me” flag, a symbol of the American Revolution. The workers then marched on the nearby TRANCON (Terminal Radar Approach Control) facility.

Hundreds of air traffic controllers from New York City’s terminals, along with supporters, rallied in East Meadow, Long Island. Gathered in a circle, they thrust their fists into the air in defiance as the deadline passed. In the middle stood six strikers holding a large, “Don’t Tread on Me” flag, a symbol of the American Revolution. The workers then marched on the nearby TRANCON (Terminal Radar Approach Control) facility.

In Detroit, 132 of the 134 air traffic controllers defied Reagan’s back-to-work order. Union Vice President Steve Conaway told the crowd gathered near the metropolitan airport, “The government and the FAA will not intimidate us. The grievances are real and we will stay out as long as it takes.”

In Lorain, Ohio, home of the Oberlin Air Traffic Control Center, the nation’s largest, more than 500 PATCO Local 203 members greeted the 11 a.m. deadline with fists in the air and the “Strike!” chant. Five hundred controllers and supporters gathered between the two terminal towers of the Twin Cities International airport in Minnesota.

About 13,000 of the original 15,000 strikers defied Reagan’s back-to-work order.

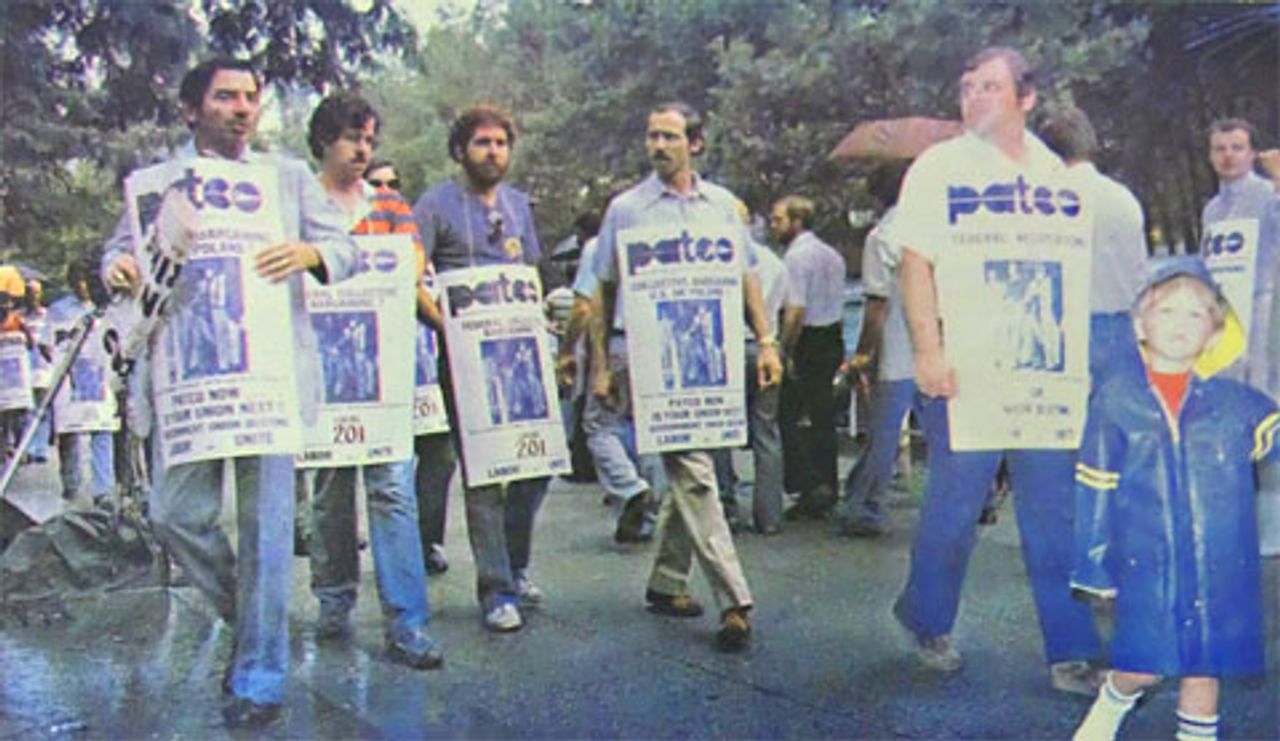

Striking PATCO members march outside the US Court House in Brooklyn where PATCO president Robert Poli was ordered to turn over the union’s assets

Striking PATCO members march outside the US Court House in Brooklyn where PATCO president Robert Poli was ordered to turn over the union’s assetsThe government responded by stepping up what PATCO President Robert Poli called its “intensive fascist tactics.” By August 10, the administration had begun proceedings to decertify the union and seize its assets. At the same time, Reagan imposed massive fines on the union to bankrupt it, and a number of PATCO strikers were arrested—one of whom, Steven Waellert, was brought before a judge in chains. There were also numerous reports of FBI harassment, including midnight visits to controllers’ homes. One wife of a PATCO striker reported that an FBI agent told her that the couple’s effort to adopt a child would be blocked unless her husband returned to work.

Within weeks, authorities had arrested dozens of strikers on picket lines, and indictments of many more were handed down. Usually these indictments related to participating in an “illegal strike,” even though the air traffic controllers had been fired and therefore, legally speaking, could not be on strike.

Carl Kern was one of seven Chicago-area controllers indicted in mid-August. Like many others who were arrested or indicted, Kern was an outspoken leader of the struggle. “I suppose I and others have been picked because of our active role and outspokenness in the strike,” Kern said. “The law is being applied very selectively against the most active members of PATCO.”

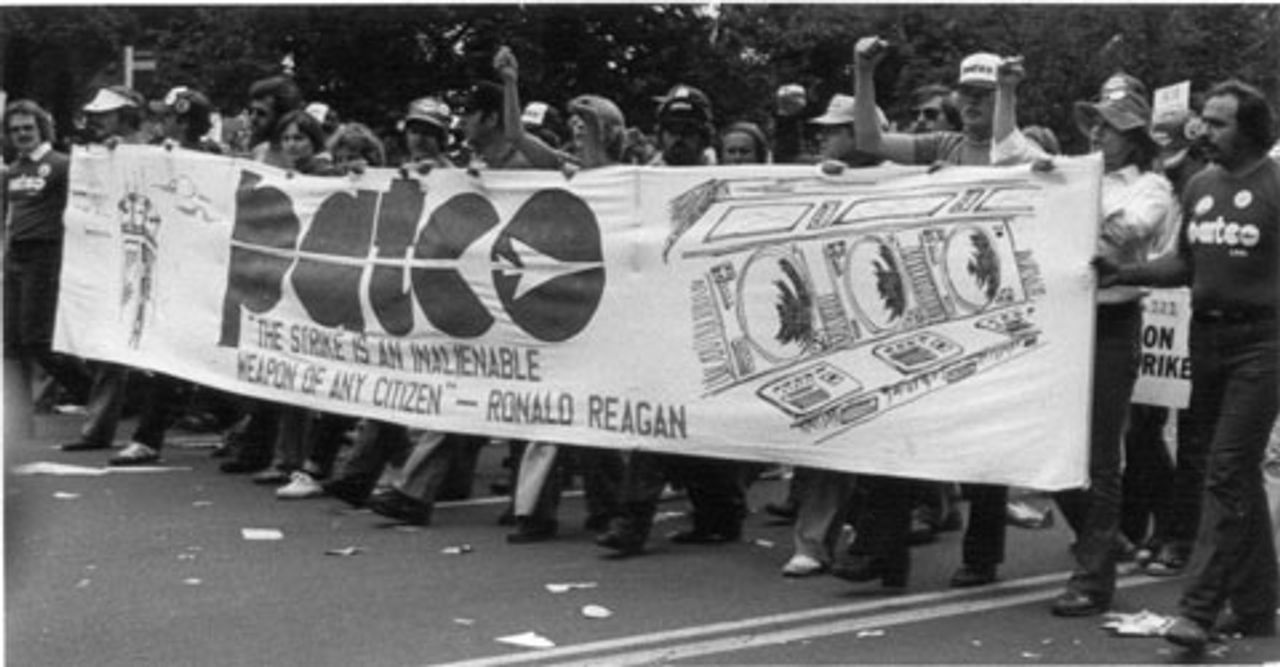

Striking PATCO members march behind their banner

Striking PATCO members march behind their bannerFAA workers who voiced support, or even associated with the PATCO strikers, were fired. Harry Brown, a supervisor at the TRANCON facility on Long Island, was fired for publicly supporting the controllers. Janice Wakefield, a teletype employee at the Aurora, Illinois control center was fired for visiting with workers on a picket line. Brian Power-Waters, a pilot for US Air, was suspended for telling passengers that their flight delay was due to unqualified workers manning the control tower.

By Monday, August 17, Secretary of Transportation Lewis declared that “the strike is over.” The air traffic control system would be rebuilt, he said, with employees drawn from among strikebreakers, supervisors, and military personnel. The Reagan administration now made clear that it would not only refuse to negotiate, but that it would not accept the PATCO strikers back under any conditions.

PATCO workers did not back down. In fact opposition to the repressive tactics of the Reagan administration continued to grow throughout August and September. On August 23, a rally of about 2,000 took place in Houston. On August 26, over 1,000 gathered at a rally in the Twin Cities.

PATCO strikers at Detroit Labor Day rally

PATCO strikers at Detroit Labor Day rallyThis was far eclipsed by the large-scale demonstration that took place on Labor Day, September 7, 1981, in New York City, where more than 250,000 workers demonstrated. The 2,000 PATCO members who marched front and center were cheered wildly. Other large Labor Day demonstrations with PATCO in the lead took place across the country, including in Detroit, where over 3,000 marched downtown on Woodward Avenue.

Then, on September 19, “Solidarity Day,” an estimated 500,000 workers descended on Washington, DC—in one of the largest demonstrations in US history. The march stretched unbroken from the Washington Monument to the Capitol building. The AFL-CIO had originally called the demonstration not to oppose the policies of the Reagan administration, but to support the Solidarity movement of Polish workers against the Stalinist regime in Warsaw.

Instead, workers seized on the opportunity of the demonstration to stage a mighty protest against Reagan. The onslaught against PATCO was front and center. Some workers held signs drawing comparisons between the state repression of the Stalinists in Poland and the state persecution of the PATCO workers.

AFL-CIO unions organized at least 3,000 busloads of workers. Nearly every union in the country was represented, as were civil rights groups and other organizations affected by Reagan’s budget-cutting. Among the largest contingents were those from the UAW, with 30,000 auto workers attending; the International Association of Machinists (IAM), who brought 20,000 members; and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, which mobilized 20,000. So large was the contingent from the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (also estimated at 30,000), that “it took more than 40 minutes for the contingent to march by, and the whole of Constitution Avenue was a sea of the union’s green and white banners, placards, flags, and t-shirts,” the Bulletin reported. PATCO brought 6,000 workers, or roughly half of those on strike.

Lee Grant, Ron May and Gary Greene outside the

Lee Grant, Ron May and Gary Greene outside thefederal courthouse

The enormous demonstration made clear that there was broad support in the working class for expanding the struggle against Reagan. However, the AFL-CIO bureaucracy categorically refused to take up such a struggle, and gradually the fighting spirit in the broader working class died down. The role of the AFL-CIO in isolating and defeating the PATCO strike, and the perspective advanced by the Trotskyists of the Workers League (forerunner of the Socialist Equality Party)—for the struggle’s expansion into a general strike and a political fight by the entire working class—will be examined in the next installment of this series.

The PATCO workers continued their struggle, for months carrying on pickets that were crossed on a daily basis by other unionized air industry workers. State repression continued to focus on the most militant and outspoken leaders, including three leaders of the Dallas-Ft. Worth PATCO local who in November, 1981, were put on trial for federal crimes. Lee Grant, Ron May and Gary Greene were sentenced to 90 days of jail each, and as a result were permanently stripped of some civil liberties. The Workers League, not the AFL-CIO, led the public defense campaign.

On October 22, 1981, the Federal Labor Relations Authority stripped PATCO of its certification to represent air traffic controllers. Now not only was its strike declared illegal and its participants blacklisted, but the union itself was no longer legal. The decision was upheld by a federal appeals court on June 11, 1982. On July 2, 1982, a federal bankruptcy court dissolved PATCO. In the summer of 1983, Greene, May, and Grant began serving th eir prison terms.

To be continued

Subscribe to the IWA-RFC Newsletter

Get email updates on workers’ struggles and a global perspective from the International Workers Alliance of Rank-and-File Committees.