PART ONE | PART TWO | PART THREE | PART FOUR | PART FIVE

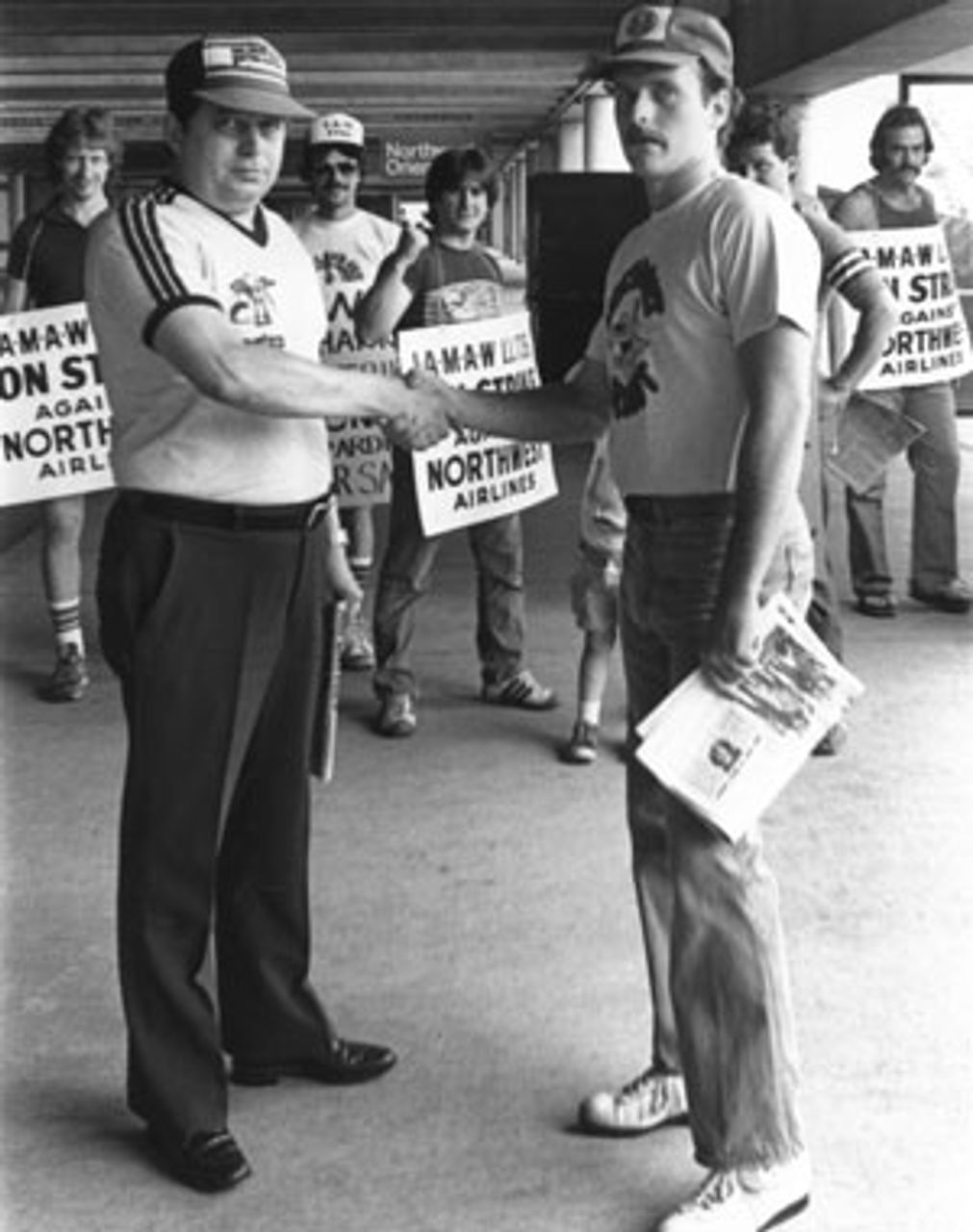

PATCO strikers on the picket line

PATCO strikers on the picket lineThe AFL-CIO trade union officials argued that any extension of the strike to cover workers in the airline industry or beyond would be “suicide.” They argued that Reagan was responsible for the move against PATCO, and so it would be necessary to appeal to D emocratic congressmen and prepare to defeat the Republicans in the 1982 elections, with AFL-CIO President Lane Kirkland referring to Election Day as “Solidarity Day II.”

The Workers League put forward a diametrically opposed position. Its call to reject Reagan’s demands, to expand the strike throughout the airline industry and into a general strike, corresponded with the thinking of workers far more than the defeatist position of the bureaucrats. But the Workers League insisted this required a political struggle against the bureaucracy and the two-party system. A new party had to be built, a Labor Party rooted in the working class and based on socialist principles. To achieve this, the Workers League campaigned among workers for the calling of an emergency Congress of Labor.

The Bulletin immediately sized up the significance of the strike. Its lead article on August 4, 1981, a statement of the Editorial Board, was headlined “AFL-CIO Must Back Air Traffic Strike: The Class Lines are Drawn.” It called on the union movement to “mobilize the strength of the entire working class to support the striking air traffic controllers against the union-busting Reagan Administration.”

The article continued: “The Reagan administration has been engaged in the last six months in an economic and social counterrevolution, aimed at repealing the social legislation and programs won by the working class during the last 50 years, driving up unemployment, wiping out all restrictions on capitalist exploitation such as safety regulations, and destroying the living standards won by decades of trade union struggle. This has been topped with the passage of the biggest tax cut in history geared entirely to the requirements of the big corporations and the rich.”

The article called for urgent action by the other unions representing workers in the airline industry, including the International Association of Machinists (IAM). This should be spread, it urged, into a general strike against the policies of the Reagan administration.

Reagan, the article noted, was “speaking for the entire ruling class,” a fact also understood by much of the news media, which whether liberal or conservative overwhelmingly condemned the air traffic controllers. As the Washington Post editorialized on August 4, “If one union, whose members work directly for Mr. Reagan, were now to achieve a spectacular wage increase through an illegal strike, that would be the end of the Reagan economic program. Investors, bankers and borrowers would all immediately conclude that, whatever his rhetoric, the Reagan Administration was not serious about reducing inflation. That’s why Mr. Reagan now has to stand absolutely fast.”

In the initial days of the strike, the controllers believed that their withholding of labor would be enough to prevail. The critical and irreplaceable nature of their work would bring the Reagan administration to negotiation, many thought, and the costs associated with training new controllers would be prohibitively high—far more expensive than a compromise wage increase for PATCO.

“People with the money, the rich, are still sitting on the ground,” Norman Hocker, a controller with 13 years’ experience at LaGuardia airport in New York City, told the Bulletin in the first week of the strike. “They’re cutting out corporate flights, and cutting back on all other flights. You have 16,000 workers holding up 27 percent of the economy.”

“I’m concerned. I would not be in an airplane today if I could avoid it,” Mitch Cook, a striking controller from La Guardia, told the Bulletin. “Right now there are three supervisors and EPDS, that’s Evaluation Proficiency Development Specialist, in the tower. Normally there are 10 people. It’s a mockery to think they could bring in military controllers to control here. The union understands what the capabilities of these men are. Our union is going to stand strong and united.”

In fact, the firing of the PATCO workers did seriously jeopardize travelers.

The FAA attributed a fatal air crash near San Jose, California, to pilot error. Two light planes on approach to the city’s airport collided in the air two miles short of the runway, killing one person and injuring two. The midair collision August 17 was the first in San Jose’s airport’s history, and it was the first in which the FAA cleared the air traffic controller—a strikebreaker—of responsibility within hours. It was also the first fatal accident in recent history in which PATCO was excluded from the investigation.

There were many more near-misses as a result of inexperienced or incompetent air traffic controllers guiding flight patterns. While the FAA hid this information from the flying public, the Canadian Air Traffic Controllers’ Union documented a list of 41 unsafe incidents on routes between the US and Canada or near the Canadian border after only one week of the strike, including a number of “near-misses.”

Reagan was willing to risk the lives of air travelers to destroy PATCO. Clearly, much more was at stake in this strike than the controllers’ own contract negotiations. Many strikers told the Bulletin that they viewed their struggle as being waged on behalf of the entire working class. Were they to lose, they said, the union-busting campaign would spread throughout the economy. For these same reasons, many controllers and rank-and-file workers in other industries realized that PATCO could not be left to struggle alone.

“The main thing is that how Reagan handles PATCO will be a precursor to how he handles strikes in general and the whole labor movement,” LaGuardia controller Norman Hocker told the Bulletin on August 5. “Here, we are making the first stand.”

Calls for joint action soon began to emerge from workers in other industries who recognized the historic nature of the Reagan administration’s assault. The Bulletin and the Workers League amplified this sentiment. On Friday, August 7, the Bulletin ran a front-page banner headline, “Mobilize Labor Behind Air Traffic Controllers: AFL-CIO Must Call General Strike!”

On August 15, Ed Winn, a member of the Transport Workers Union Local 100 Executive Board in New York City, addressed a rally of some 400 controllers and their supporters near JFK Airport. Winn, also a leading member of the Workers League, read a resolution to be introduced at the next TWU executive board meeting calling for emergency action in support of PATCO and demanding a general strike by the entire AFL-CIO.

The same week, Houston Local 15 of the IAM sent telegrams to Kirkland and IAM President William Winpisinger demanding a general strike be called.

Even union officials were compelled to acknowledge the sentiment for a general strike. Ralph Liberato, a Michigan AFSCME official, when asked on October 16 by the Bulletin whether or not the Michigan AFL-CIO would initiate the call for a general strike in support of PATCO, said, “There’s been an awful lot of talk about this among our members and a lot them are asking why we don’t do it.” Similarly, on August 26, David Roe, president of the Minnesota AFL-CIO, told a Bulletin reporter that “the feeling for a general strike is strong and growing.” Claiming that he would support one, he said the ultimate decision rested with the federation’s executive council.

In late September, Kirkland admitted that there was overwhelming rank-and-file sentiment for a general strike. “I have never gotten as much mail on any issue in my life. I’ve gotten a tremendous amount of wire, letters, cards,” Kirkland said. “About 90 percent are pro-controllers and about 50 percent of those denounce me for not calling a general strike.”

As early as August 7, PATCO President Robert Poli had sent telegrams to all AFL-CIO unions asking that they honor the picket lines that were in place in hundreds of airports around the country.

This did not happen. In fact when the strike began the AFL-CIO Executive Council and General Board was in session. The meeting concluded on August 6 with no plan for assisting PATCO. On the contrary, the union heads sent clear signals to the Reagan administration that they were prepared to collude in the crushing of PATCO.

AFL-CIO President Kirkland publicly rejected the call for a general strike, declaring, “It’s easy to be a midnight gin militant and call for a general strike, but if you’re a responsible leader you have to appraise the consequences.”

Interviewing IAM President William Winpisinger, a reporter for the Bulletin asked if he had any intention to call a support strike among his members in the airline industry. If even one other section of the unionized airline industry had struck—the airline mechanics of the IAM, the pilots, the stewardesses, the baggage handlers—the position of PATCO would have been immeasurably strengthened.

Boston PATCO local leader showing support for

Boston PATCO local leader showing support forstriking Northwest machinists on their picket line

However, Winpisinger stated, “It would be committing suicide for 40,000 of my members,” adding, “It might even be sounding the death knell of the whole union.” In subsequent years, the other unions in the airline industry would, one by one, force massive concessions on the workers they claimed to represent.

In a similar vein, UAW President Douglas Fraser said that the air traffic controllers strike “could do massive damage to the labor movement.”

The Bulletin commented August 7, “What extraordinary logic! [Reagan] is attempting to impoverish millions of working class families, but Fraser warns that to fight this government ‘could do massive damage to the labor movement.’”

John J. O’Donnell of the AFL-CIO-affiliated Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) provided public support to the Reagan administration. He repeatedly pledged that air travel continued to be as safe after the strike as before, a position contradicted by a safety commission of his own organization that found “a definite safety hazard” created by unqualified controllers. In August O’Donnell negotiated wage cuts of 10 percent for Pan Am pilots and a 30 percent increase in flying time per month for United pilots.

The perspective of the AFL-CIO, to pressure Democratic politicians into backing the strike, only served to demoralize the strikers and disorient the broader working class. There were some pronouncements of support for the strike from Democrats, but just as many condemned the strike. Detroit’s Democratic mayor, Coleman Young, held up by the UAW in particular as a “friend of labor” and a former autoworker himself, accused the strikers of “holding the nation hostage” over “outrageous” demands, going so far as to call Reagan a “hero” for standing up to PATCO.

Solidarity Day, Washington DC, September 19, 1981

Solidarity Day, Washington DC, September 19, 1981The massive Solidarity Day rally in Washington showed that there existed in the working class the desire to fight Reagan’s policies. But that event proved to be the first and last significant step the AFL-CIO permitted against the administration’s union-busting drive and class-war policies.

After the union was officially decertified in late October, the AFL-CIO publicly capitulated. In the words of UAW head Fraser, “The war is over.” In response, the Bulletin called for the November national convention of the AFL-CIO to “call Fraser to order and reject his position as defeatism.”

The Bulletin wrote: “What the Convention must face up to is the fact that there is no fighting Reagan without breaking decisively with the Democratic Party and mobilizing the working class politically against capitalist policies through the construction of a Labor Party based on the trade unions.”

Instead, the biennial convention convened and dispersed having taken no concrete action to assist the controllers. This proved, the Bulletin noted, “the total bankruptcy of the bureaucracy’s policy of class collaboration. Historically it is finished.” It continued, “However, the more clear it becomes that the defense of basic rights won by the working class requires a struggle against capitalism, the more desperately does the bureaucracy cling to capitalist policies.”

In December, Poli wrote to Kirkland, pleading with him not to “let PATCO die.” Kirkland did not respond, and Poli resigned on December 31.

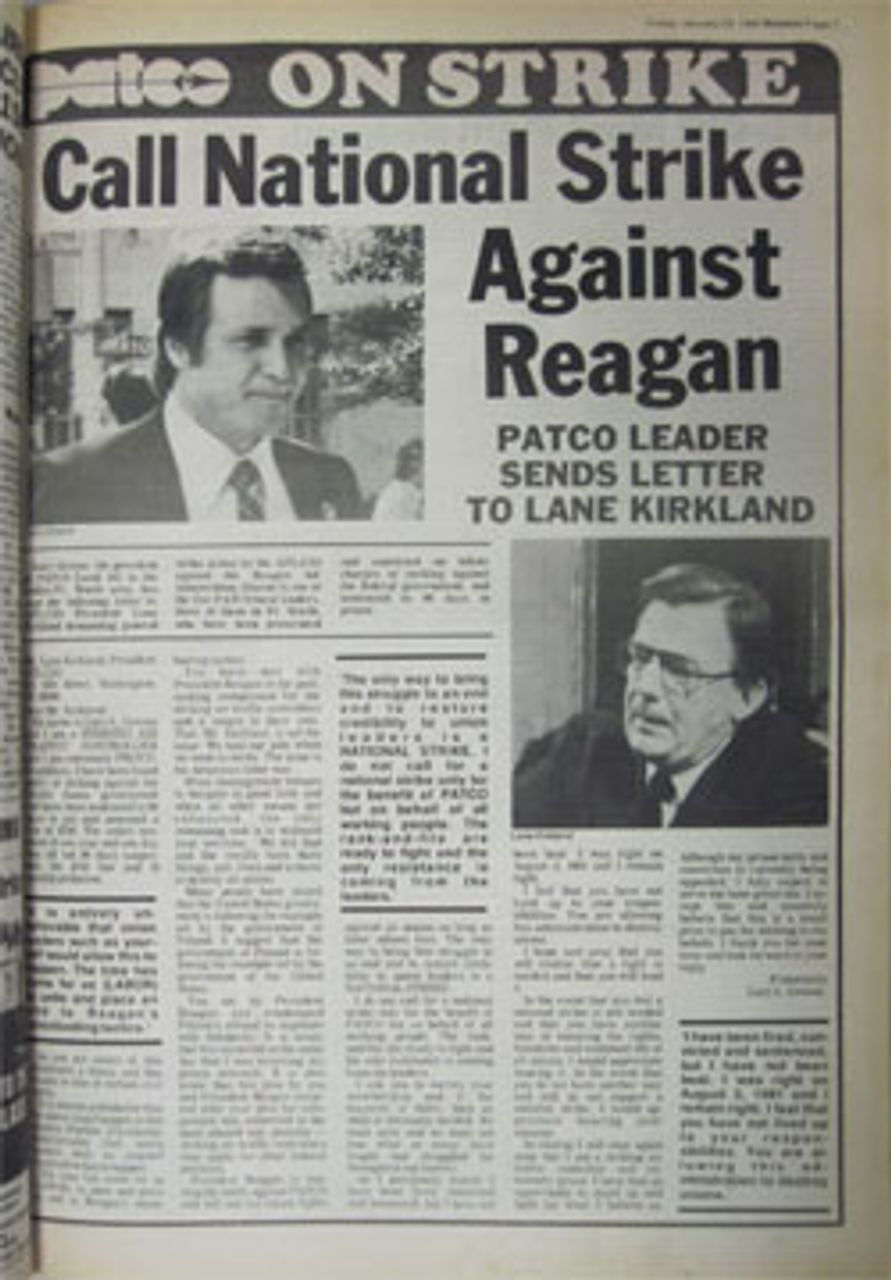

Bulletin issue reporting Gary Greene's open

Bulletin issue reporting Gary Greene's openletter to AFL-CIO head Lane Kirkland

On January 29, 1982, Gary Greene, one of the Texas controllers sentenced to prison for his role in the strike, wrote to Kirkland asking him to call a general strike.

“President Reagan is winning his battle against PATCO and will win his future fights against all unions as long as labor allows him. The only way to bring this struggle to an end and to restore credibility to union leaders is a NATIONAL STRIKE,” Greene wrote. This letter was endorsed by a meeting of 180 controllers in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Kirkland’s office responded by claiming there was no support for a general strike, and suggesting that unions redouble their efforts to elect Democrats in the 1982 elections.

To be continued

Subscribe to the IWA-RFC Newsletter

Get email updates on workers’ struggles and a global perspective from the International Workers Alliance of Rank-and-File Committees.